We Need To Sing About Mental Health

April 19, 2015

by hotelconcierge

Apr 19, 2015

(trigger warnings: depression, anxiety, self-harm, suicide, anorexia, chronic pain, drug abuse, gender norms, anything and everything mental health related. Don’t read this unless you’re willing to be offended.)

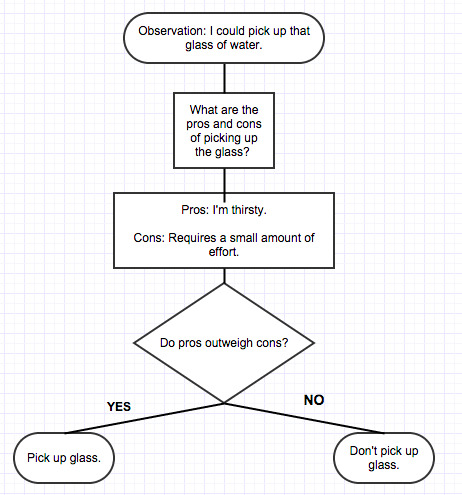

I. Every so often, my Facebook news feeds pops up an image like this:

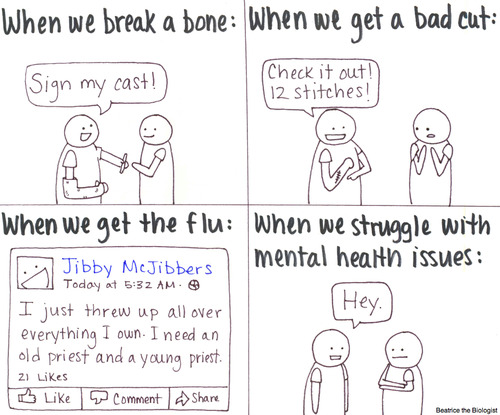

Or this:

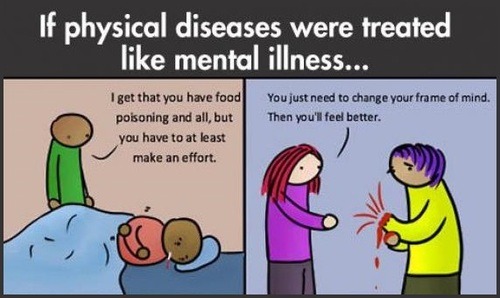

Or this:

And so on.

For the most part, I agree. It’s unfair that the system doesn’t treat mental illness as seriously as physical illness and the lack of mental health resources is disgraceful. Mental illness is everywhere, and it takes a grave toll on those whom it affects [1]. No one should feel afraid or ashamed to seek care.

Stigma is bad. But here’s the thing: I don’t know anyone who disputes this. I don’t know a single person who is pro-stigma. And while the internet is full of jerks, any mental health-related Google query pops up 1,000,000 times more pleas to Talk About Mental Health than links in support of stigma, and for every Youtube troll telling depressed people to buck up, I see fifty variants of the above images [2].

So if most people are against stigma, why does it still exist?

Here’s the first clue: every time one of those images pops up in my news feed, the person who posted it turns out to be a young woman.

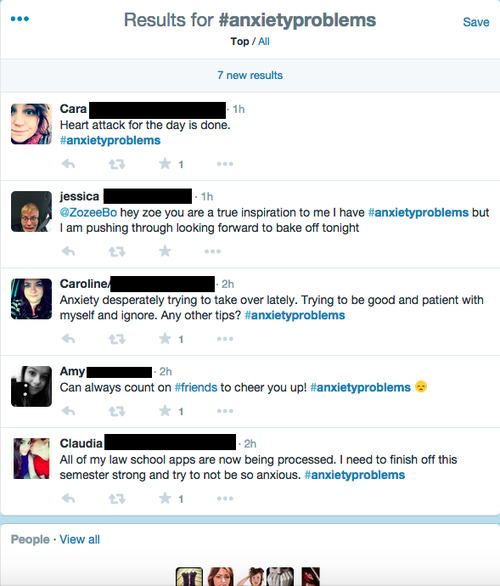

I searched the hashtag #anxietyproblems on Twitter. Women are 53% of Twitter’s userbase and 1.7 times more likely to have an anxiety disorder, but that skew doesn’t explain the first page of Twitter results, which showed that #anxietyproblems had been posted by thirty-seven women and one man. (Then I got bored and stopped counting.) How about depression? Conventional wisdom holds that women experience depression at twice the rate of men [3]. On the results page for #depressionawarenessweek, I found a 6:1 ratio of female to male posters. That alone would be significant, but…

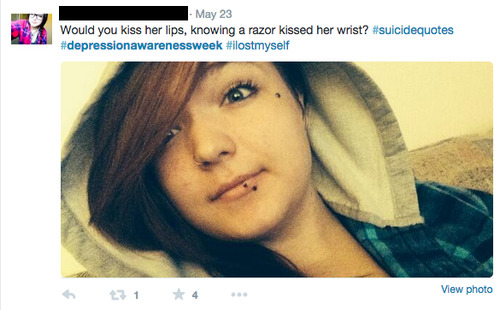

About half of the male tweets were unreadable collages of blue text plugging a start-up, self-help book, or other commercial product. Another 25% were from dads, preachers, and other forty-plus year-old men who had a noble concern for community wellbeing but did not seem to be talking about their own depression. In contrast, the women were young (say, 15-24), talking about THEIR depression, and occasionally posting stuff like:

Oh boy.

II.

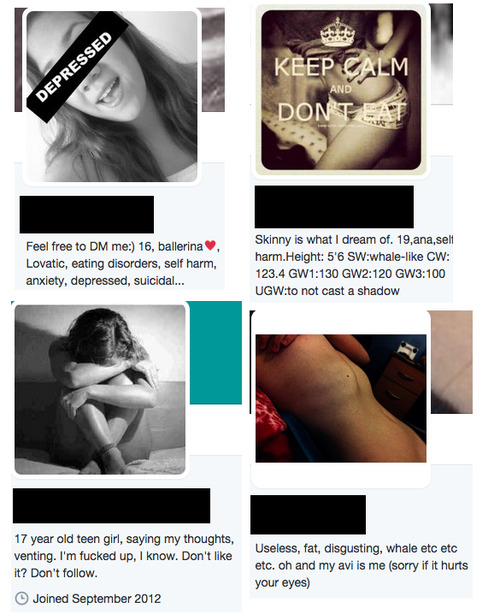

Compared to men, women talk about mental illness frequently, publicly, and candidly. On Twitter, you often see self-bios like:

This is a random sample—I found hundreds of these profiles without even trying. You never see men with bios like this: the Twitter search results for “depressed guy” are women who have depression talking about how they have a crush on a guy. I am not trying to diminish the suffering of these young women, I am just pointing out that it is “normal” for them to talk about it. “But some men talk about mental illness too!” Sure, like this guy.

I found this video on a #PopularOnYouTube playlist of “Stories That’ll Restore Your Faith in Humanity.” I should have known better, experience has taught me that “Restores Your Faith In Humanity” is a euphemism for “Crushes All Hope For Society’s Repair.” On the other hand, check out this guy’s cheekbones! His accent! His eyebrows! His flawlessly beanie’d hair! His ah, relatability!

The other day, my friend confided in me. She said that she’d be feeling depressed. And worse than that, she’d been feeling incredibly alone in her situation.

She confided in him. I bet he’s such a good listener. Did I mention that he has gorgeous eyelashes? Check out the self-conscious grin at 11 seconds in, as he says:

This struck a chord with me, because not too long ago, I too was feeling depressed. And I too was feeling incredibly alone, and somewhat ashamed about my feelings.

He never again mentions his own mental health. At 0:32 he gives a perfect smile and coyly admits that “Mental illness is a thing. It exists,” signaling to the viewer that we have moved from personal confession to Charming Young Person In Center of Frame Says That Bad Societal Problem Is Bad, that we have gone from feel-bad-about-problem to feel-hope-about-solution, i.e. the structure of every other inspirational video ever made. If he had been talking about global warming the sequence of facial expressions would have been the same. He spends the rest of the video talking about his friends, saying that stigma is bad, listing mental illnesses, saying that stigma is bad (again), and concluding with:

It’s okay to suffer from a mental illness. But it’s not okay to not talk about it. Because then we achieve nothing.

What does he imagine “talking about it” looks like? Because at the end of this video, I have no idea what he had been feeling depressed about, what it felt like, how he got over it, etc. I don’t want to come down too hard on young Mr. Darcy. He’s not doing anything bad- but it’s not going to convince anyone to talk about mental illness who wasn’t planning to talk anyway. Maybe I should take on a video meant for my demographic.

From the TED Talk video description:

Kevin Breel didn’t look like a depressed kid: team captain, at every party, funny and confident. But he tells the story of the night he realized that – to save his own life – he needed to say four simple words.

To quote a friend: “If talking yourself out of suicide counts as ‘saving a life,’ then I should be a national hero.” But okay, fine. Kevin opens the video by stating that has struggled with depression for many years, and then clarifies:

Real depression isn’t being sad when something in your life goes wrong. Real depression is being sad when everything in your life is going right. That’s real depression, and that’s what I suffer from.

So that’s what real depression is. Better get working on that DSM-6! Never mind that depression is disproportionately common in people with chronic pain, diabetes, Parkinson’s, cancer, HIV, anxiety, tobacco abuse, alcohol abuse, Asperger’s syndrome, body dysmorphic disorder, anorexia nervosa, OCD, avoidant, dependent, paranoid, histrionic, or borderline personality disorder. Those people don’t have real depression. Continue, Kevin.

And to be totally honest, that’s hard for me to stand up here and say. It’s hard for me to talk about. And it seems to be hard for everyone to talk about, so much so, that’s no one’s talking about it.

So brave. It can’t be easy having a TED Talk with 3,000,000 views and then using the ensuing hype to get >100 college guest speaker gigs and a book deal with Random House.

And we have a tendency, as a society, to look at that and go “So what?” We look at that and say “That’s your problem, that’s their problem.” Well, two years ago, it was my problem. Because I sat on the edge of the bed, where I had sat a million times before, and I was suicidal. I was suicidal. And if you were to look at my life on the surface, you wouldn’t see a kid who was suicidal. You would see a kid who was the captain of his basketball team, the drama and theater student of the year, the English student of the year, someone who was consistently on the honor roll and consistently at every party. So you would say I wasn’t depressed, you’d say I wasn’t suicidal, but you’d be wrong.

Look, I agree that depression has a chemical basis and that even people with a seemingly idyllic life can be depressed. But does Kevin expect me to believe that he was suicidal for no reason? Check out the above list of depression correlates. It’s possible that Kevin was depressed ex nihilo, but I doubt it, and I’m particularly skeptical because Kevin says “everything was awesome” over and over again. People with strong internal self-worth do not repeatedly proclaim how great they are. That’s what insecure people do.

You have to admit that Kevin’s speech is awfully convenient for his ego. He is telling himself (and the millions of inspiration-hungry TED viewers) a story in which his life was perfect except for the depression, like it was a virus he just happened to have caught, like it had nothing to do with his thoughts or behavior. In this way, Kevin avoids having to admit flaws, make the audience uncomfortable, or risk anything real. He also earns a get-out-of-jail-free card for any personal failures. “I’m normally confident and funny—gosh darn that pesky depression!” “I would have gone to the party, but, shucks, depression.” “I swear, babe, this never happens. But you know…”

I feel sympathy for Kevin, who I’m sure is fighting some serious inner demons, and I don’t think that video is doing anything bad. But it is not useful, and it’s not useful in the same way that nearly every male-curated “Let’s talk about mental health!” video is not useful. Choose all that apply. The video:

- a) shows the speaker as confident, attractive, and “not your typical mentally ill person.”

- b) suggests that the speaker is heroic just for talking about mental illness.

- c) willfully ignores any details of the speaker’s life or internal monologue that may have contributed to his mental illness.

- d) does not describe recovery or any treatment pursued; gives no actionable advice whatsoever.

“We need to talk about mental health.” Okay. You first. III. Let us assume that a serious stigma exists against people with mental illness. Does that mean everyone in the world agrees with this stigma?

Of course not. The #depressionawarenessweek people and TED talk listeners certainly don’t agree with it. It’s likely that a few people endorse stigma, many don’t, and most people are in-between, not actively anti-stigma but not consciously discriminatory. Isn’t that true about…everything? If there is such an outgroup, where is the in-group? Where is DepressionCon? Where are the Social Anxiety Pride parades?

Answer: that’s why we invented the internet.

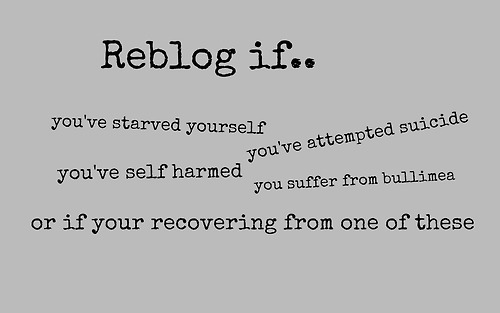

A two sentence quip about a political issue says nothing about the issue but speaks volumes about the poster. For the #sadgirls, mental health stigma has to exist, else there’s no basis for identity, for community, no “them” to oppose “us.” “I’m fucked up, I know. Don’t like it? Don’t follow,” Twitter user DepressedBitch says, i.e. I don’t want your pity, i.e. being depressed doesn’t compromise my social status, i.e. who says depression can’t be chic? Self-loathing is an aesthetic. That doesn’t mean that the unhappiness is fake, it just means that some people have figured out how to broadcast it in a high-status way. This quasi-glorification of mental illness can be absurd (see: the “suicidal trans-vegan demiromantic multi-souled latte” self-labeling that is rampant on Tumblr) or dangerously self-reinforcing (see: pro-ana), but, for a bunch of sad teenagers, it’s better than feeling alone.

As a rule, women are the ones social media bonding over identity markers, and I think this tendency explains part of the Talk About Mental Illness gender skew [4]. That said, men invented sports teams and the console wars, so it’s not like guys are incapable of bro-ing out over superficial similarities. So why don’t men—and the majority of women who do not have black-and-white Twitter profile pictures—talk about mental illness?

Except they do: Men only disclose when sheltered by anonymity. (This, as much as anything, is why 4chan and Reddit are so male-dominated.) Reddit has a searchable archive, so I’ve taken my examples from there. Here’s a post titled “Nearing 30, weighed down by anxiety and depression, no path ahead of me.”

Today is not a low day, that was yesterday. I am up, cleaning, and listening to music. But my mind is busy, as always. I don’t have a job. I haven’t for about two years now. I don’t have a driver’s license, because driving is terrifying to me. I dropped out of college after 2 years, 8 years ago. I still carry a bit of the debt, which has invariably changed my life since then. I lost my last job because of panic attacks. I never made enough money to see a psych, and once i did, they were polite but dismissive of my needs. I was on medication, prozac, until two days ago. I move around a lot, so as not to be a burden to the people who basically support me. I moved, my medicaid lapsed, my food stamps were canceled. So, despite what they say about not going ‘cold turkey’ when it comes to meds of this sort, i basically have to. I also lost the meds i take for my thyroid condition, which is actually more important to me, honestly. I come from a poor family, and realized early on that you have to have something to get something. Doctors terrify me because it always meant being further in debt with no guarantee of actual care. I’ve had times when i could not afford to have a job, and, to this day, i don’t understand how people pay for cars/insurance/gas. Despite these pressing needs, despite the obvious state of fuck-upped-ness that anxiety and depression causes, i cannot qualify for disability, as far as i can tell. Unless i call a hospital and threaten suicide, no one will step in and help me. I can’t even continue to see a psych. Basically, i could kill myself right now, and there would be precisely zero people to stop me. Because i’m lost. I’ve officially slipped through the cracks. I will not win the lottery, i will not save a life and become internet famous, i will not be that homeless person that someone hands a check to. I lost my hopes and dreams a long time ago. I lost that warm fuzzy feeling from people comforting me with words when i realized nearly everyone says the same thing, over and over. There is no path. No point. And no point to me writing this. I will not bother with a TL;DR because it doesn’t really matter if anyone sees it. Just that it exists. No moral of the story, no snappy punchline. Just me. Fading.

Dude, try to keep your mental illness to 140 characters or less. Reddit is full of similar confessions—I recommend these posts on schizophrenia, PTSD, and OCD—but my favorite is “I am short, I am losing hair rapidly and I have a small penis - I own the trifecta of ugliness. I am a virgin and have 0 friends. I just need to vent.” Can you imagine that as a TED Talk?

Reddit user isthereanyhope1 looked like a depressed kid: short, balding, no friends, virgin, small penis, and poor. But he tells the story of the night he realized that – to save his own life – he needed to say four simple words.

How can this person, stigma or no stigma, talk openly about his mental illness? If he posted a context-free “I have depression” on Facebook, for example, I’m sure that the comments would be benign and supportive, but they would also be totally useless. (“Go see a therapist.” He already knows he should do that.) If the poster went into more detail about his unhappiness—short, balding, small penis, and so on—then he might get more constructive advice (help with his body image), but he’s also marked himself as someone who will never be dateable, employable, or invited to parties, and this will probably make his depression worse. Even if we ignore this guy’s specific issues, there’s a world of difference between sanitized Depression™ and the unsexy lying-in-bed-not-eating-not-sleeping-wanting-to-die realities of a depressed person’s day-to-day existence, realities which tend to harsh on the social vibe. And if talking about depression is hard, just try opening up about your auditory hallucinations.

The anti-stigma campaign has the same defect as the anti-bullying movement: it can stop kids from taking your lunch money, but it can’t make them be your friends. Chronic illness makes you look weak, weakness provokes pity, pity is the cool-killer, and the #depressionawareness gender bias is all about pity. For women, pity and attraction are antithetical, but most men don’t care (“if she’s hot”) and a few actually prefer pitiable women, craving the power that comes from being the one good thing in someone else’s life. This is pathological, yes, but talking about mental health won’t fix it. Take another look at that first comic. No one judges you for having a broken wrist or the flu, but those are acute, self-limiting conditions that say nothing about who you are. Compare this to people with COPD, HIV/AIDS, obesity, tuberculosis, irritable bowel syndrome, celiac disease, epilepsy, and sickle cell disease, who report that they feel “stigmatized” and are hesitant to reveal their condition. “We need to talk about mental health.” Well, why don’t we talk about irritable bowel syndrome?

The reason we don’t talk about mental health goes beyond stigma. It isn’t unique to mental illness. It’s present with anything that makes you look weak. It’s present with anything that affects the way you interact with others or others interact with you. And it isn’t going away anytime soon.

IV.

I would like to take a moment to talk about how mental illness sucks.

"Depression is not sadness,” goes the saying. And it’s true. Sadness is far from the worst feeling in the world. Sadness can be fun: girls cuddle up and cry to Titanic, boys get drunk and text ex-girlfriends, and we all love to hear songs about lost love. We adore the novelty of emotion, and even as we suffer, our preconscious smiles and adds a chapter to our life story. We choose sadness, because sadness is a thousand times preferable to boredom.

There is nothing good about boredom. No one has ever said “It was a very boring time in my life, but it taught me a lot about myself,” because boredom’s only lesson is to avoid boredom at all costs. Perhaps it’s a bug in the human reward circuit, that highs and lows are so preferable to a steady zero, but it’s a bug so deeply ingrained as to be unfixable. Binge-drinkers and adulterers aren’t stupid, they know they’re making poor decisions, they just care about intensity of emotion more than direction. Happiness is ephemeral, sadness is temporary, entertainment fades; boredom is always waiting.

But pain is worse.

You can never understand how bad pain is except when you’re currently feeling it. Then then it hits you—this is that thing, this is that thing that’s worse than anything else. God, you wish that you were only bored. Pain cuts in line and heads straight to the bottom of Maslow’s hierarchy. In 1984, Winston says:

Never, for any reason on earth, could you wish for an increase of pain. Of pain you could wish only one thing: that it should stop.

And sure, you can endure any single moment of pain—that’s why people cut, to make the pain predictable, controllable—but if the pain doesn’t go away, if you can’t see the end, if you look into the future and see an infinity of single moments that you will have to endure, then you will be destroyed. Have you ever had the flu? I mean a legit influenza, not some poser rhinovirus. To say that it is unpleasant does not do it justice. There’s an ache that cripples every myocyte, a nausea that permeates every molecule, a fatigue that saps you of the desire to eat or move or think. The symptoms are so bad that even though rationally you know that you’ll be better in a week, part of you doesn’t believe this, part of you thinks that one week is an impossibly long time, and so you find yourself thinking “I want to die,” not really meaning it, of course, but unable to help the feeling that literally anything would be better than existing in the material plane.

Depression feels like you have the flu.

I mean this literally: the nausea, discomfort, and lethargy of clinical depression feels exactly like a bad grippe. The current trendy hypothesis is that depression is biochemically caused by immune-mediated inflammation, and “cause” is a loaded word, but the somatic symptoms of depression are so similar to influenza-induced malaise that I doubt it’s a coincidence. Anxiety doesn’t feel like the flu, anxiety feels like a heart attack, complete with chest pain, shortness of breath, nausea, lightheadedness, and “sense of impending doom.” In this way, anxiety and depression are more akin to physical pain than to emotional upset, and they both trigger the same desperation, that aversion-to-existence and internal screaming of make it stop, make it stop, I’ll do anything to make it stop.

The first treatment for pain is: “Ouch.”

Communicating your pain alleviates it, at least for a second. I don’t think this is cultural: I think this is older than that. At the risk of stepping into untestable evo-psych waters, it makes sense that conveying “My hand is burned,” to a fellow tribesman would have benefits both to the sufferer (“I need help”) and the listener (“Huh, fire is hot”), and that, over millions of years, this could become a reflex.

However, aside from waving an immolated limb, there is no good way to communicate pain.

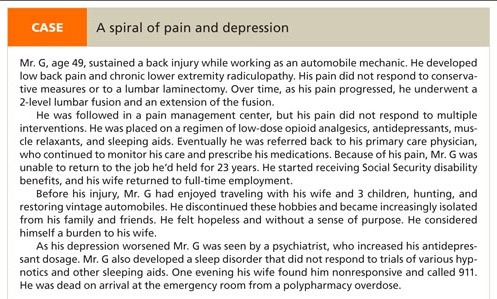

As part of an incredibly ill-conceived “Pain as the 5th Vital Sign” initiative, if you are triaged at any Emergency Room in the United States, the nursing staff are mandated to show you the above image and ask that you pick a number. Here is the dialogue that ensues:

“On a scale from 0 to 10, where 0 is no pain at all, and 10 is the worst pain imaginable, how bad is your pain?” “Hmm…10.” “10? Are you sure? 10 is the worst pain imaginable. Like, you are actively being run over by a train. Is your pain really a 10?” “Ugh, I guess you’re right. Okay, 9.5.”

And then the guy in “9.5/10″ abdominal pain goes back to eating chips and playing Candy Crush on his iPhone. The nurse wants to call him on his bullshit, but how can she be sure? Maybe he has a perforated appendix and he’s just keeping his composure remarkably well. Next patient is a middle-aged woman who is sobbing about her 2 cm laceration and “10/10″ pain. Seems ridiculous, but how can you tell? What if she actually has more nociceptors? Can you call someone a wuss if they’re actually feeling more pain? And then, of course, just to confuse things, a guy comes in with 6/10 pain despite having five snapped ribs, a broken vertebrae, and a popped lung. People are terrible at objectively quantifying their pain, and that’s when they are trying their best to be honest. Often they aren’t. People lie about pain all the time: to get narcotics, for workman’s comp, to be “taken seriously.” People lie about mental illness as well [5]. Since it’s legally-iffy to discharge someone who is actively suicidal, homeless people often report suicidality in the hopes of getting a bed for the night. Drunks threaten suicide and then ask for lunch, opiate addicts threaten suicide if you won’t help them detox, and one colorful BDSM aficionado “overdoses” on Motrin, gets placed in a guarded room, tries to escape, gets tackled by security, and orgasms, loudly.

So maybe self-report is not the best method to assess someone’s suffering. You can guesstimate pain by the person’s behavior, which rules out Flappy Bird-associated abdominal pain, but selects for people to writhe and scream for attention, meaning you have to guess whether or not the writhing is genuine, and soon enough you’re playing Mafia: “Well, she’s not writhing, but maybe she knows that I’d expect her to writhe, or maybe…” (n.b: Anyone who claims to have a “high pain tolerance” will immediately follow this with a request for Dilaudid.)

And so whenever possible, doctors ignore the patient’s stated pain and instead treat based on the severity of the underlying condition. A broken femur gets more of the good stuff than a sprained ankle, even if the former reports 5/10 pain and the latter reports 11/10. Which seems reasonable. Except…

If you’re a young, healthy person, then the flu, awful as it feels, isn’t dangerous. Migraines hurt like stink but don’t cause any lasting damage. Back pain is the leading cause of disability worldwide, but no one has ever dropped dead from sciatica. Heroin withdrawal is infamous—like every ounce of happiness and hope is being torn from your body—but if you stay hydrated and don’t aspirate then you’re going to be fine. Trigeminal neuralgia, arguably the most painful condition known to man, has essentially no negative consequences aside from pain; then again, that pain is pretty bad. “Suicide is the definitive treatment,” as they say.

Conversely, people with gastrointestinal bleeds and a hemoglobin of 3, a paper cut away from death, feel “a bit dizzy when standing up.” Heart attacks and pulmonary emboli can be asymptomatic. Diabetics develop oozing foot sores and don’t notice for weeks. Sepsis can manifest as “feeling weak” and a brain bleed as “my hand is numb.” Practically any symptom, no matter how minor, can indicate cancer.

What’s my point? My point is that I’m considering getting a neck tattoo of “THE MAP IS NOT THE TERRITORY.” You can’t accurately assess your own pain, pain is easily faked, bad pain doesn’t mean that you have a life-threatening illness, and trying to determine if someone else has “a real problem” based on their reported suffering is like looking at a Xerox of a crayon drawing of a compressed .jpg of a map which, incidentally, is not the territory. If someone reports a 10/10 headache, no meaningful data can be inferred. And if someone reports “severe anxiety, so bad that I can’t leave the house, which is why I need a Xanax prescription and SSDI”…well, society is going to be a little skeptical.

What’s particularly frustrating about this absence-of-evidence is that it affects even the people who are on your side. If I tell you that “Every inch of my body is in constant, fiery-dagger pain, the source of which is undetectable by any medical test known to man,” you may sympathize (“That sounds awful,”) but it will be very difficult for you to empathize (“Oh, definitely. Fiery-dagger pain. We’ve all been there.”) And because I can’t get you to empathize, that automatic reflex to communicate pain won’t be satisfied, and I will not get the relief of being understood.

In this sense, mental health stigma does exist, although it’s not unique to mental health: people with chronic pain face a similar struggle. Again, the problem is not that people will shame you for your pain and tell you to pull yourself together—although this does sometimes happen—the problem is that even if they try to listen, most people still won’t get it. Honestly, how can you blame them? You have no evidence. Pain is a symptom, anxiety is a symptom, depression is a symptom, and symptoms are all inside your head. For someone with chronic pain or mental illness, this is torture. Why do I feel so awful all the time if it’s all in my head? Why can’t I just stop feeling this way?

If you’ve ever had this thought loop, perhaps this will be a comfort: everything is inside your head.

All perception is fallible—Cogito ergo sum, man—but if you’re willing to pretend you’re not a brain in a vat then so am I. Pain is the sixth sense: major depression and clinical anxiety are disorders of perception. You can’t turn off your perception of pain any more than you can turn off your sense of smell. Fibromyalgia is neuropsychiatric—it responds to antidepressants—but that doesn’t mean people with fibromyalgia aren’t feeling real pain. Same thing for irritable bowel syndrome. Acupuncture is pseudoscience, but that doesn’t mean that it doesn’t successfully treat symptoms. (Consider: acupuncturists spend around an hour with each patient, physicians spend an average of 20.8 minutes.) Depression (here, here, here), asthma (here, here), arthritis (here, here), and many other conditions are alleviated by placebo. Success is not happiness, misfortune is not misery. Emotion and reality do not have a linear relationship.

Pain is bad. I consider myself anti-pain. And in this respect, I concede that “talking about mental health” is a useful tool, because even if it doesn’t yield actionable advice, empathy is still analgesic. And I will also admit that, with regards to pain palliation, “stigma” is worth fighting against—communication alleviates pain, and stigma impedes communication. (Although, again, stigma is far from the only hindrance to communication—see section III.)

But treating the symptoms is not the same as treating the disease.

V.

There is a consistent pattern to how ordinary people get addicted to drugs.

From a recent NPR article, “For Those Suffering Chronic Pain, The Hardest Part Is Convincing Others”:

LEIDY: My name is Kate Leidy, and I have fibromyalgia. Fibromyalgia is a musculoskeletal - I always have a hard time saying that word. It’s basically a nerve disorder.

MARTIN: …she can trace it [the pain] back to a deep emotional wound when her two-month-old baby died from prematurity complications. This was a few years ago. And since then Kate has suffered pain pretty much everywhere.

LEIDY: I take Butrans. I take Lyrica. I take Wellbutrin. I take Cymbalta. I take Vicodin, Percocet and ibuprofen. MARTIN: Kate Leidy’s doctors have been resistant to keep prescribing her heavy painkillers. There are obvious concerns about addiction. LEIDY: You sort of have to make your case for taking pain medication. You have to go to your doctor with sort of your list of notes and defend your right to relieve your pain.

Doctors have a number of reasons to be hesitant about prescribing narcotic pain medication [^6] for fibromyalgia: not only are opioids [^7] addictive, it’s not clear that they actually help. However, the article’s comments support Ms. Leidy’s perspective:

I have had fibromyalgia for over 10 years and have constant pain. I’ve forwarded a link to the story to many of my friends - some who still don’t understand why I don’t travel to see them as I did in the past…There is one part of the chronic pain story I think you missed. Those in chronic pain taking narcotics don’t necessarily become addicted to the opiates. In fact, most do not.

Yes, if opioids are the medicine that works, they cause dependence, just like prescription steroids and blood pressure pills. But make no mistake, dependence is not the same as addiction…People with chronic pain do not get high from their medicines. Rather, they are rendered as close to normal as they may be. This allows them to get out of bed, to be mothers and fathers, and to go to school or work.

These comments draw a distinction between drug dependence—the spiral of increasing tolerance and withdrawal symptoms—and drug addiction, with its “uncontrollable cravings, inability to control drug use, compulsive drug use, and use despite doing harm to oneself or others.” They argue that there is a difference of motive: people with chronic pain don’t take opiates to get high, they take opiates to function. From the same comment section:

Addiction should be considered a separate problem. Essentially, it refers to a behavioral disorder. Most users of opiates for pain management do not act like addicts, ever.

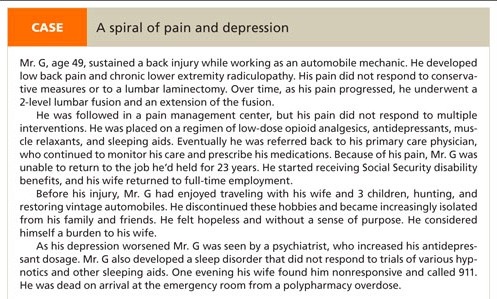

This statement is wrong, dangerously wrong, but before I tear it apart I want to reiterate that chronic pain is life-ruiningly awful. Chronic pain patients have an increased rate of depression [^8] and a startling risk of suicide; they experience hopelessness, anxiety, fatigue, loss of libido, loss of jobs, and loss of friends. And they hurt. All the time.

I empathize with the MAKE IT STOP urgency of pain, and I don’t blame anyone who wants the strongest analgesia possible. But the line between drug dependency and addiction is tenuous at best, and motivation doesn’t count for much when you’re passed out, turning blue.

Chronic pain patients don’t use drugs to get high. Thing is, neither do most drug addicts. Late-stage addicts don’t use to feel good, they use to avoid pain. “Cravings and compulsive use” are not a sign of weak will, but an inevitable response to increasing tolerance and physical dependence: the few users who are “chasing the dragon” or whatever are amateurs, and the shits-and-giggles phase of drug abuse doesn’t last long. Veteran heroin users will tell you that they don’t shoot up for the euphoria—they barely even get high anymore—they shoot up to stave off a hellish withdrawal. Pot starts off as a cure for boredom, then it stops being fun, and then its the only escape that’s left. Alcohol starts off as a treatment for anxiety, but within a few years its the only thing that works for anxiety, and soon enough anxiety isn’t the problem anymore, because you’ve lost your job and you can’t walk from the shakes and if you don’t drink a half-bottle of vodka before lunch you’re going to have a seizure. This is the pattern of drug addiction: a temporary solution becomes your new problem.

Heroin, the best analgesic and ultimate pleasure, has a withdrawal syndrome characterized by severe pain and a soul-crushing despair. Marijuana withdrawal causes nausea, vomiting, excess salivation, and anhedonia. Alcohol and benzodiazepine withdrawal causes tremors, severe anxiety, and seizures. (n.b: This can kill you.) It seems like a cosmic joke that a drug’s withdrawal symptoms are the exact opposite of that drug’s effects [^9], but it’s a joke with a solid biochemical basis: your brain changes its “set point,” so that it releases a given amount of neurotransmitter only for a much increased dose of exogenous chemicals, which is to say, you build up a tolerance.

And so—going back to chronic pain management—the problem is that when you start an opioid regimen you have pressed the red button on a time bomb. Sooner or later you will build up a tolerance and need a higher dose of medication. And a higher dose. And an even higher dose:

I really need some help getting my tolerance back down to not such batshit levels. I am at the point where snorting 40mg of oxymorphone doesn’t have much of an effect on me. I can still operate after railing 120-130mg oxymorphone. I’d say I use about 300mg of oxymorphone a day. Obviously I get [sic] a prescription or I would be beyond broke.

To which redditor SubstanceAbuser replies:

Heroin really is your best route here… but it costs too much and it’s super fucking addictive. I can’t even get high from 80 mg oxys, even if I shot it. However, I strongly recommend you don’t do heroin. I would get some suboxone and try to quit.

The OP then posts:

I really do want to quit but I’m not sure if my orthopedic injuries will allow me to function without some sort of narcotic. If you would have told me I would have found myself in this situation when I first hurt myself 4 years ago I would have never believed you. These pills are truly the devil. I absolutely hate what I have become.

This person’s opioid tolerance is so high that he considering using heroin in order to function on a day-to-day basis: if that doesn’t make him an addict, then I’m not sure what an addict is. But the fun doesn’t end there, because even if you survive withdrawal and quit using narcotics, your body is used to them: opioid-induced hyperalgesia.

Now that I’ve been off of opiates for about 6+ months, I can not deal with pain. Not only am I sensitive to physical pain (which is to be expected of course) but I can’t even think about pain without getting squeamish and literally sick to my stomach. I can’t watch movies or shows where people are injured because I get sick just watching it. (Reddit)

So when you start on opioid pain medication, not only are you going to receive diminishing returns on analgesia, you are moving further away from ever having permanent relief from your chronic pain.

I fractured my spine playing football and have had chronic pain that I will have to deal with for the rest of my life ever since. At first I only used them for pain like they were meant to be used, and I made extra sure not to over do it, but eventually you WILL become addicted because you will need them to reach a state of normalcy. I was to the point of taking three hydrocodone at a time to get any effect, and after a month my doctor said I needed to go to the hospital because of the damage I did to my liver from the APAP [Tylenol]. He put me on oxycodone without APAP after I recovered, and after a year and a half of a crippling addiction I decided that I would rather live with pain for my entire life than die at 30 from opiate addiction. After going to rehab and getting myself on track I’m finally getting better and I do attribute much of my recovery to the use of medical marijuana. Sadly I’m not even 18 yet and was in rehab as a 16 year old. I know my case was a worst case scenario, but I never thought that I would become an addict like I was. I wish you the best of luck, and please don’t do what I did. (Reddit)

This is a complex issue and I don’t want to oversimplify it. The literature is filled with contradictory and poorly constructed studies—my gestalt is that opioids provide good short-term pain relief but start to lose efficacy and run a risk of tolerance/addiction in the long-term. It does seem clear, however, that opioids are significantly less effective in patients with pain of ambiguous (read: psychiatric) etiology. I don’t kid myself that this spiel will convince any of the hardcore I-need-Percocet-for-my-fibromyalgia advocates, who I’m sure are full of comebacks about how I couldn’t survive one day in their shoes, etc. Fine. I’m libertarian about drugs: if you want 20mg Xanax and 200mg Oxycodone daily, that’s your prerogative, just don’t puke on the couch. I don’t preach abstinence: narcotics have an important role in controlling severe, breakthrough pain, and I think that other substances can be educational and fun if used occasionally. All I’m saying is that if there is something you reach for every time the going gets tough, then you will build up a tolerance to that thing; if you’re not careful, tolerance will lead to dependency, dependency will lead to addiction, and addiction will make it very, very difficult for you to solve your original problem.

And so. We need to talk about mental health.

Blogger ozymandias271—who prefers gender-neutral pronouns—is a sharp essayist for whom I have a great deal of respect, and whose opinions I disagree with reliably. Ozy suffers from anxiety, depression, and borderline personality disorder. During a recent live-blogged depressive episode, ze made the above post, along with several posts expressing suicidal ideation.

As a consequence of these posts, concerned Tumblrites began to send well-wishes and reassurances. Ozy was not pleased.

Why would Ozy, a luminary of the modern rationalist movement, write these posts? It doesn’t seem rational at all. If you don’t want people to help, why are you posting suicidal thoughts on the internet?

The cynical answer is “attention,” but this doesn’t ring entirely true. First, as Ozy points out, there are plenty of ways to get attention that don’t involve declarations of self-loathing. Second, as previously noted, anyone who feels the need to lie about suicidality to get what they want has some sort of mental illness; at the least, they are not feeling optimistic. Third and most interestingly, Ozy’s statements seem to be an extreme example of a behavior that is exhibited by just about everyone: “venting.”

“Just listen for a moment, I need to vent,” = “I’m not looking for a solution, I just want someone to empathize.” I am guilty of this; unless you have just arrived from ancient Sparta, you are guilty of this as well. It’s the ouch reflex: communication alleviates pain. The perverse thing about venting, though, is that it is less satisfying when the listener responds with a solution. “Stop trying to help! If you really understood how I feel, you’d understand that there is no possible solution that could ever be implemented by anyone ever.” Hence Ozy’s irritation.

Obviously there’s a difference between publicly professing suicidality and complaining to a friend that your boss is a jerk. The difference isn’t one of structure, though—it’s a difference of tolerance.

Here’s how this tolerance plays out.

One day, a depressed person feels even more depressed than usual. He vents to a family member/significant other. The family member takes it seriously, the depressed person feels understood, and his mood temporarily improves.

This repeats several times.

The depressed person has another spike of hopelessness. He talks to a close friend but for some reason doesn’t get his usual rush of relief. He feels that the listener isn’t taking him seriously—and maybe that’s true, Boy Who Cried Wolf and all that—but it’s equally likely that, without realizing it, the depressed person has built up a tolerance. And so the depressed person acts a little bit dramatic. He cries, he stares at the floor, he yells, he screams, he hints at suicidal thoughts. He’s not lying, he’s just method acting. Eventually, the listener proves that she “gets it”—she starts crying—and the depressed person feels a little better.

This repeats several times.

The depressed person feels worse than ever. He spends a week posting about suicidality on his blog, telling anyone who will listen but becoming increasingly frustrated that no one understands. He fantasizes about showing everyone just how miserable he is. He wants to show them how they’ve made him feel this way: by shunning him, by refusing to listen to him, by supporting the unjust structures of society. He imagines that if he did die, his death would teach them a lesson. He imagines how sad they would feel at his funeral. He fantasizes about lying supine in the street and staring into space, blocking traffic, blocking the crosswalk, an act of protest against the universe. He fantasizes about being understood, about not feeling alone in his suffering. But, lying on his bed, he realizes that no words can possibly make anyone get it. He has to do something. Not suicide, because even though he hates living he he doesn’t quite want to die, but something just short of it. Something to show them how much pain he’s in. So he goes to the bathroom, downs a bottle of pills [^10], and calls 911.

This repeats several times.

Patient well-known for depression/SI, borderline, PTSD, polysubstance abuse, has been seen 3Xs w/in the past 6wks for overdose all with admissions to the CCU. He arrives by ambulance today d/t acute polysubstance OD on psych meds. He crushed up three different psych meds of known amounts and took them all simultaneously at 1145. When medics arrived, he handed them a sheet of paper with the names, doses, and amounts of each pill stating, “I took these.”

The depressed person has attempted suicide five or six times now. During his last ER visit, the nurse rolled her eyes and said something about “you again.” The depressed person can’t think about anything other than his depression and how much time he’s wasted being depressed, which makes him even more depressed. He feels worse than ever but cannot communicate this: anything he says will be perceived as attention-seeking drama, a prelude to another pathetic attempt. He can’t get anyone to understand, and even if he could get them to understand, there is nothing they could do to help. The problems that once made him unhappy are not relevant anymore. Now his problem is depression. That’s all he is now: a depressed person. He cannot imagine a way out of his situation. And so he buys a rope…

It is a cultural myth that expressing emotion is inherently a Force for Good. It’s a myth taught by parents (“Go ahead, let it all out. There’s no such thing as a bad feeling”), supported by television (where emotions have to be externalized or else not exist at all), and expedited by the internet. But it is a myth. Communicating emotion is a drug—useful on occasion, tolerance-inducing, and addictive. This, in essence, is the problem with therapy—not all therapy, but definitely the chronic, insight-oriented, therapist’s-business-card-in-wallet type. Even if it’s not helping, you’ll still want more.

A 2001 study published in the Journal of Counseling Psychology found that patients improved most dramatically between their seventh and tenth sessions. Another study, published in 2006 in the Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, looked at nearly 2,000 people who underwent counseling for 1 to 12 sessions and found that while 88 percent improved after one session, the rate fell to 62 percent after 12. Yet, according to research conducted at the University of Pennsylvania, therapists who practice more traditional psychotherapy treat patients for an average of 22 sessions before concluding that progress isn’t being made. Just 12 percent of those therapists choose to refer their stagnant patients to another practitioner. (NY Times)

This is also the flaw of inpatient psychiatric hospitalization. I’ve seen this a half-dozen times: patient checks into the psych ward feeling depressed and suicidal, gets started on medication, gets intensive daily therapy, does group-sharing activities, does artistic expression activities, feels much better, signs paperwork saying that she feels non-suicidal, leaves the hospital, gets in a taxi home, panics, downs a bottle of pills, and checks back into the psych ward.

As part of a larger clinical trial, patients (n = 103) with major depression without suicidal ideation at hospital discharge were followed for up to 6 months while receiving study-related outpatient treatments. Fifty-five percent (n = 57/103) reported the emergence of suicidal ideation during the outpatient period, with the vast majority (79%; n = 45/57) of these patients exhibiting this problem within the first two months post-discharge. (Source)

We conducted a national population-based case-control study of 238 psychiatric patients dying by suicide within 3 months of hospital discharge, matched on date of discharge to 238 living controls…Forty-three per cent of suicides occurred within a month of discharge, 47% of whom died before their first follow-up appointment. The first week and the first day after discharge were particular high-risk periods. (Source)

The risk of suicide in the first week after discharge is higher than the risk of suicide at the time of hospital admission. This is a withdrawal syndrome. And so, going back to Ozy:

If you are an addict, the solution is not to procure more drugs. And Ozy is an addict: if ze doesn’t talk about mental health in the most dire way possible, then ze doesn’t feel safe and cared for. By relying on external succor to treat pain, Ozy has taught zirself to be helpless. For example:

Ozy believes that mental illness is best modeled as a disability. Ze self-describes with the word “neurodivergent,” which probably isn’t meant as a bleak satire of the social justice movement but totally is. From zir essay:

Neurodiversity is essentially the radical notion that not everyone has a brain that works the same way.

The medical model of neurodivergence works something like this: just like some people can have sick bodies, some people can have sick brains…If your brain is sick, you should go to a doctor and receive treatment that will make you not sick anymore.

At the same time, the medical model isn’t very good for people who are going to have weird brains for the rest of their lives.

Ozy’s pulling a motte and bailey with the definition of neurodivergent: one moment it means “not everyone has a brain that works the same way; don’t be a jerk,” the next it’s “all mental states are equally valid; accept your current state and don’t try to change.” I don’t think everyone should become “neurotypical”—neurotypical people don’t exist, by the way—but I posit that not all neurodivergence is created equal.

It [the medical model] contributes to a Fantasy of Being Neurotypical, similar to the Fantasy of Being Thin. You can spend your entire life trying to become a neurotypical person and failing–or you can accept that you’re neurodivergent and try to live the best life you can as a neurodivergent person. It is possible to have a happy, fulfilled life and be badbrains as fuck. And for those of us who have incurable mental Stuff, it is necessary.

No. I don’t think it’s possible to have “a happy, fulfilled life” while clinically depressed, I don’t think it’s a fantasy to have obsessions and compulsions reduced to a minimum [^11], and I don’t accept that mental stuff is untreatable. With regards to unwanted medicalization, Ozy gives the examples of ABA treatments for autism and ADD medication for kids. I mostly agree with zir on this—children can’t give consent for psychiatric treatment—but the blame should not fall on the treatments (which do help some people), it should fall on the parents: supply only exists because of demand. Fine, but Ozy is accusing the medical model of unfairly pathologizing all neurodivergence. This is absurd. Autism and ADD have pros and cons, but most neurodivergences unequivocally suck [^12], and pretty much everyone who has depression or schizophrenia would rather they didn’t. It makes logistical sense to categorize these conditions as illnesses, as this allows mental healthcare to be covered by insurance and gives doctors grounds to prescribe medication. A good rule-of-thumb: does [insert condition] negatively impact your life or the lives of those around you? If it does, consider getting help. Otherwise, don’t sweat it.

The social model of mental illness works like this: some people are not able to do things that other people can do; this is called “impaired”. A person who cannot walk is impaired. Some impaired people are not accommodated by society; this is called “disabled”.

What does the author want to be true? Ozy distinguishes between “illness” and “disability” because illnesses are treatable, and disabilities, in general, are not. Ozy’s philosophy is the evolution of We Need To Talk About Mental Health: mental illness = Not Your Fault, mental disability = Not Even Curable. This is scientifically unsound—in this study, 70% of depressed patients recovered after eight months of outpatient treatment, and most mental illnesses show improvement with therapy—but it’s critical to Ozy’s identity. If mental illness is treatable, then getting help, to some extent, is Ozy’s responsibility, but if mental illness is immutable, then it’s society’s responsibility to take care of Ozy.

I don’t think there is anything wrong with social support and I don’t think there’s anything wrong with the occasional accommodation. But I would caution against being the type of person who needs to be accommodated, if you can at all avoid it. Once you start needing, it gets harder and harder to stop. I get the desire for trigger warnings, but when you demand that other people not trigger you, you are giving them power over you. Every bully in the world now has an easy way to hurt you: you have made yourself weak. It’s a perfectly reasonable choice to not attend a party because you feel anxious, but if you claim that you can’t attend a party because you have “an Anxiety Disorder,” you are refusing to own your choice, you are deciding that you have no power over your future, and you are solidifying that this is who you are: a person who is incapable of attending parties. Feeling anxious is temporary, Anxiety is an identity. Not doing the dishes because you feel depressed is understandable, not doing the dishes because you have Depression is a self-fulfilling prophecy. I get that defining yourself as Depressed eases the pain of depression—it lets you avoid the constant mental gnashing of “maybe I’m not doing enough,” “maybe I’m not trying hard enough,” it lets you accept your condition. Do you want to accept your condition, though? Or do you want to stop being depressed?

Sometimes, treating the symptoms makes the disease worse. When you define yourself as Disabled, you define yourself as someone who cannot solve his or her own problems. With time, this will become your default response to pain. “I can’t do anything, someone please help.”

This is a trap, and it will ruin you. I’m not saying “stop defining yourself by your mental illness” because I’m a neurotypical jerk. I’m saying it because I have tried the path of disability and it does not work. Mental illness is not your fault, but it is your responsibility. The only person who can fix your problems is you.

Ozy is dependent on other people for care and praise and relies on labels to avoid accountability for zir own behavior. The result is that Ozy is, always, perpetually, a victim.

If a significant other tells you that he/she is “unable to understand that I don’t deserve to be mistreated,” get a pre-nup and don’t have kids, because the divorce is going to be ugly. Ozy’s helplessness permeates every aspect of zir being.

Zir social life:

Zir day-to-day sustenance:

Zir sex life:

And zir employment (or lack thereof):

I’ll say it again: you do not want this. There’s nothing morally wrong or shameful about using mental illness as a disability, it just doesn’t work—a temporary solution becomes your new problem. Ozy identifies as genderqueer, but the only reason ze gets away with this behavior because ze a) is young and b) has female genitals. This coping mechanism will not last. Ozy knows this, Ozy is smart, but ze’s addicted to zir identity, to zir defense mechanisms, and ze can’t imagine being anything else.

Ozy, to zir credit, is working on cognitive behavioral therapy and exposure response therapy. I wish zir the best of luck, but I think that Ozy’s outlook will make the process much tougher than it has to be. Ozy doesn’t want to change, ze wants the world to change.

I want the world to change too. But I wouldn’t count on it happening any time soon.

VI.

I mean no ill will towards Ozy or anyone like zir. Life is hard, really really hard. The struggles of mental illness take a lifetime to solve. I am reminded of the Serenity Prayer:

God, grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, The courage to change the things I can, And the wisdom to know the difference.

This prayer neglects to mention that nobody this side of Gautama Buddha has been granted “the wisdom to know the difference.” Few things are more difficult than deciding whether you need to change. If you focus only on treating the underlying disease, not allowing yourself the comforts of confession, self-acceptance, and the occasional crutch to lean on, then you will tear yourself apart for every mistake, get nowhere, and give up.

But the alternative is no better. If you focus only on treating the symptoms, then you will spend your life on the verge of tears, always looking for reassurance or distraction, always feeling that someone else—society, your parents, your genetics, your friends—has wronged you, always waiting for a prize, for a lover, for something or someone to wipe away your sadness, to tell you that you have suffered enough, that you are good enough, that this was all test, which you’ve passed, and now you can be happy.

This is one thing of which I am certain: suffering does not guarantee a payoff. Some people spend their whole lives miserable and then they die. Do not let this happen to you.

VII.

I dislike criticism that fails to provide an alternative. So here’s some conjecture. Maybe it will help.

As a case study, let’s talk (unipolar) depression. What is depression?

Depression is a chemical imbalance.

Absolutely. Then again, everything is a chemical imbalance. Some cases of depression seem entirely chemical, e.g. depression after traumatic brain injury; however, most people are quite vocal about the mental and physical ailments contributing to their misery. It seems likely that in the majority of cases negative thoughts cause biochemical changes which in turn cause the somatic symptoms of depression. This is supported by the fact that therapy works.

Depression is an evolutionary adaptation: a prompt to ruminate, a source of insight and strength.

I find this hypothesis kinda amusing—I’m pretty sure that in the Era of Evolutionary Adaptedness, depression would lead to death-by-Sabertooth almost immediately, regardless of how much it benefited your pre-agriculture Ascent of Man aesthetics. The evidence for depressive realism is weak, depression predicts a decline in physical health, and depressive fatigue makes it difficult to pour a bowl of cereal, nevermind allowing “the individual to concentrate on long-term goals.”

Depression is the human form of learned helplessness.

This is plausible. Repeated, inescapable suffering --> the human body decides “I must be sick” --> chronic inflammatory changes --> symptoms of malaise, fatigue, etc. The question is, given similar environments, why do some people “learn helplessness” while others don’t?

Depression is a bug in the software.

We can work with this. Bugs can be debugged.

Here is a basic decision tree:

(This decision tree might happen in a conscious thought-stream, or it might happen so fast that you don’t really process it.)

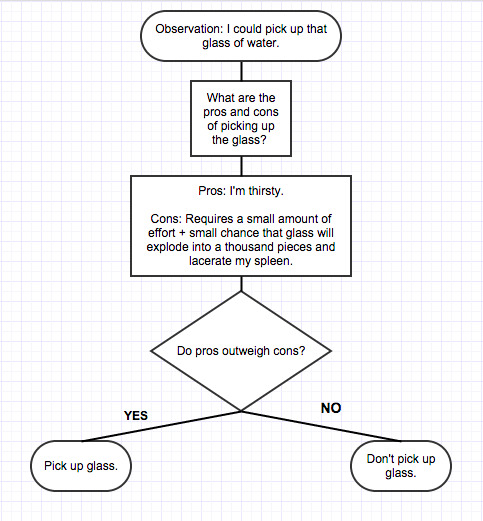

So let’s say you pick up the glass of water, and, by some freak-of-probability aberration, it explodes into a thousand pointy shards. Whoa, weird. And so now, even though that was a fluke, your decision tree might be:

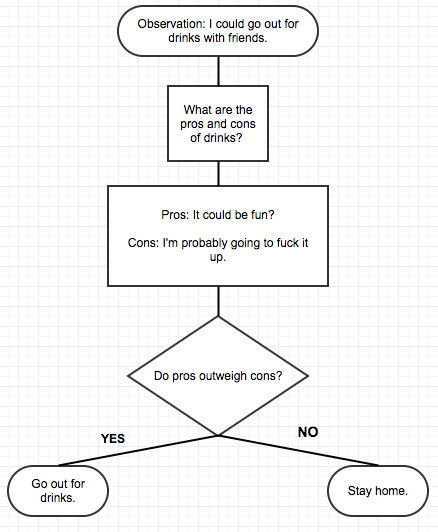

A few days later, you get into a fender-bender with the Dalai Lama while backing out of a parking space. A week after that, you mix up “discrete” and “discreet” in a letter to your grammar-conscious grandmother. The day after that, you have a panic attack while trying to flirt with a Trader Joe’s cashier; on Friday, you fail to feign appropriate interest when a co-worker shows you pictures of her vacant-eyed grandson, and a week later, the Dodgers go on a six-game losing streak, which really isn’t your fault at all, but still seems to reflect negatively on your prospects. And so, when you’re invited to go out for drinks with friends:

So you stay home and spend the weekend feeling bad that you don’t have a social life; more that, you feel bad that you’re the type of person who is too lame to have a social life. You spend the next week days feeling bad that you spent the weekend feeling bad, and the next month feeling bad that you spent a week feeling bad, etc. Every slightly-flawed decision gets confirmation-bias added to this chain of mistakes, intensifying your feeling of personal deficiency.

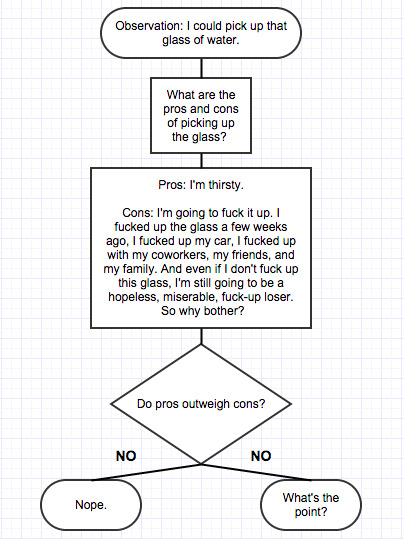

Eventually:

And once this becomes unconscious, so that every new sensory input triggers an inexplicable cascade of hopelessness, you have depression.

I know this seems like an exaggeration, but if you talk to depressed people, you hear this sort of thing all the time.

Therapist: Why do you think you feel depressed? Patient: I don’t know. No reason. I just feel hopeless. Therapist: What do you feel hopeless about? Patient: I don’t enjoy anything. I’m unloveable and I’m going to die alone. Therapist: Why do you think you’re unloveable? Patient: I’m useless. I’m ugly. Therapist: Why do you think you’re ugly? Patient: I don’t know. Therapist: Do you like any parts of your appearance? Patient: I like my eyes. I like my hair, I guess. Therapist: What do you dislike? Patient: I think my toes are weird. My feet in general. Therapist: How so? Patient: They’re too boxy. Therapist: So you don’t think anyone could love you because your toes are too boxy? Patient: …Yes. Therapist: … Patient: …

Some people with depression have suffered really horrible trauma, don’t get me wrong, but even in those people depression lives in irrational thought loops. If you were burned with a crack pipe as an infant, why should that have anything to do with how you feel now? Why should that influence your future? “Well, ever since childhood, I’ve felt anxious and scared when…” Totally reasonable, but understand that the thought loop is the source of your current depression, not the trauma itself. I am not dismissing the severity of your suffering, I am saying that you can treat it.

Depression is an error of pattern recognition and of attribution. In the “glass of water” example, the depressed person a) assumed that a series of random shit-luck events were related, and b) assumed that these events were a reflection of his competence and worth. Neither of these things were true. The halitosis-concerned co-ed extrapolated from “people sit far away from me” to “bad breath” to “unloveable” to “hopeless”; this pattern is obviously false. And someone with depression due to distant trauma has incorrectly surmised that a) being the recipient of trauma signifies something about him/her as a person, or b) that the trauma is going to happen again.

So. How do you break the pattern?

Prescribed antidepressants.

Antidepressants are not a happy pill. (You’re thinking of morphine.) Antidepressants are not even a cure for depression. Antidepressants—specifically, SSRIs and tricyclics [^13]—are numbing medications that reduce the fatigue, aching, and malaise associated with depression: they do not affect thought loops, only the feelings attached. This can lead to a peculiar state in which one runs through a mental parade of nightmares and self-loathing while giving these thoughts the emotional weight of an order at Taco Bell. (Similarly, antidepressants decrease anxiety without improving social skills and diminish sex drive without decreasing the desire to have sex.) Prozac and friends affect emotional peaks first, both positive and negative, and while this is preferable to depression, it definitely places a cap on max happiness.

I don’t want to make antidepressants sound dystopian, though. Antidepressants treat pain—including physical pain, incidentally—in a safe and nonaddictive way [^14]. And hopefully, if you aren’t feeling awful 24/7, you will spend less time feeling-bad-about-feeling-bad, and so can go out and do whatever is required to smash negative thought loops and move on with your life [^15].

The reset button.

Reddit trips out over these every week: Ketamine cures depression, LSD cures depression (and alcoholism), and so does Psilocybin. These are pretty different substances, and I suspect that their success has less to due with their individual effects and more to do with the fact that they get you totally blitzed. During a drug trip, and for days to weeks afterwards, the brain has to piece itself together and remember how to think. Since this is such a foreign process, the brain doesn’t automatically resume it’s self-loathing loops. I suspect that this is the reason that ECT works: why else would a jolt to the brain magically cure depression? Unfortunately, the effect doesn’t last. Relapse rates are very high for the two most studied interventions (ECT and Ketamine), and, anecdotally, repeated LSD and Psilocybin trips also have diminishing returns. (Plus, Ketamine has horrific long-term effects.) I’m not saying that hitting the reset button is never useful, but it won’t fix the problem for good.

Have someone point out that having boxy toes does not make you unloveable.

I have a perhaps-irrational belief that perfectly executed cognitive behavioral therapy can solve any problem. I mean, if you could identify unhelpful, negative thoughts and then not think them, what problem could you possibly have?

But the keywords above are “perfectly” and “executed.” Cognitive therapy is hard. It’s one thing to have someone tell you, “No, trust me, you’re totally fine”; figuring out how to believe this is another thing entirely. CT is exhausting: it uses up mana, or willpower, or some neurotransmitter with a fixed per-day allotment. (Sleep helps.) The behavioral part of CBT isn’t any easier [^16]—it boils down to “I know this activity will make you unhappy, but you should do it anyway.” It’s not surprising that about a quarter of patients drop out of CBT treatment. If you’re depressed and you fail at a given instance of CBT, then you’re going to beat yourself up for failing; however, this itself is a distorted thought, so you’ll beat yourself up for beating yourself up, but then…

And I guess that’s my worry regarding this essay. When you give an unhappy person a “solution” for their unhappiness, there’s a fair chance that you are giving them a new reason to feel unhappy. My goal is not to make people unhappy—seriously, you’re not allowed to feel guilty or ashamed after reading this—but I understand how frustrating meta-judgment can be.

So here’s what I’ve got.

We need to sing about mental health.

Depression is not sadness, it is hopelessness. A depressed person can feel happy (“It’s not gonna last”), but it is impossible to feel hopeful and depressed at the same time. The easiest way to have hope is to be okay with anything.

The anti-stigma campaign conflates symptoms with disease and confuses disease with identity. Depression is a chronic illness, sure, a disability, okay, but when it comes down to it, depression is a series of thoughts. Each thought lasts a moment. And a thought, lasting a moment, is not who you are.

Detachment is the key. Pretend that your feelings are happening to someone else, like you are controlling the videogame of your life: accept that you feel depressed without accepting that you are depressed. “I feel worthless and suicidal today. That’s interesting. I wonder if I can change this feeling?” So you do CBT and it doesn’t work. “That did not change my feeling. Huh, good to know.” If something goes wrong, it is not your fault. It has nothing to do with you. It’s just a thing that happened, once. Maybe it will go right tomorrow. Maybe it won’t. You are not allowed to look backwards, not even for a second. The past has no influence over what you do now. And you can’t look too far forwards, or you’ll draw patterns where none truly exist. For as long as you are depressed, you must loosen your grip on induction.

Eventually, if you keep trying, if you’re doing something, anything, you will start to feel better. Depression is hopelessness: the breakdown between effort and reward. When you rediscover that your actions have value, it feels like a miracle. “I just did the dishes! Holy shit! I made myself breakfast and I ate the breakfast and now the dishes are clean!”

From Reddit:

At first, it was just about putting jeans and a decent shirt on instead of wearing pajamas all day. It was calling my parents just to see how their day went, which I never did before because I was too consumed with my own issues. It was making a list of three small tasks (pay a bill, vacuum the living room, do the dishes, etc.) for the entire day. After a few weeks of that, I expanded things a little more. Now I stated exercising, but even then it was only like walking around my block a time or two. Now I made my list five small tasks a day. Now I called my parents, but I also called a few of my buddies I wished I had kept in better touch with.

Eventually, I found that doing all of these little things made me feel really, really good about myself. I was so proud that I could wake up and get out of bed before 9 am. It became my drug. I wanted to feel more of that. I wanted to feel like I accomplished something every day. There were plenty of bad days along the way. I just made sure to always be aware of myself. Always be able to identify when the bad days happen and make sure the next day is better. Make sure I maintain my momentum.

Ultimately, that momentum turned into positive habits. I not only escaped the jaws of depression - now life was actually … good? This has been the weirdest thing of all. My goal all along had been to just not have a shitty feeling about life. I had never considered having a happy outlook a possibility. But here I am. I not only lost all of the weight I put on after college - I’m actually in the best shape of my life (and that includes my time as a Division I athlete). My wife and I didn’t just save our marriage - we’re in twice as good of a spot today as we were on our wedding day. My friendships and relationships with my family are flourishing. I’m at a place that I never thought was even remotely possible.

In short, my advice is this: Maintain momentum. Every little bit counts. It might take a spark for you to take that first step, like it took Robin Williams dying for me. But once you take that step, make sure you keep moving, even if it’s just shuffling your feet a few inches. Also, it’s OK to be selfish. By that, I mean that it’s OK if the only reason you’re asking your mom how her day went is because you are trying to fix yourself and deep down you really don’t care how her day went. That’s fine when you’re getting started. All that matters is that you chase that feeling of accomplishment. Once you get it, never look back.

One last thing—Do you ever notice how artists start out pessimistic and bleak and then steadily go uphill? Modest Mouse did this, Tom Waits, Leonard Cohen, Neil Young, Radiohead, Spiritualized, Of Montreal, Andrew Jackson Jihad, Dr. Dre, DOOM, Tyler the Creator, and the Wu-Tang. Maybe this is sample bias, but I’m pretty sure the down-up trajectory is more common than its opposite, which includes, uh, Beck and Vincent Van Gogh.

Obviously there’s lots of confounders here (e.g. money and fame), but I think this trend hints at something therapeutic. It’s not about “creating art”—it’s about identity.

It seems minor, but there is a vast difference between being an Artist (who happens to be depressed) and a Depressed Person (who happens to putz around in Ableton). An Artist can stop being depressed, a Depressed Person can only stop making art.

Defining yourself differently gives you the opportunity to change. Your identity doesn’t have to be an Artist: it can be a Performer, a Parent, a Partier, an Intellectual, a Healer, or even a Villain. Art is the time-honored answer to pain, but anything that lets you become someone new works.

And so I don’t begrudge those who want to communicate feeling, who want to figure out who they are and announce it to the world. But don’t just talk about mental health. Sing.

Footnotes

Disclaimer: this essay is going to focus on depression and anxiety over other mental illnesses. Three reasons:

a) Depression and anxiety are common. Surveys have found 12-month and lifetime prevalences (in the U.S.) of 6.7% and 13.2% for major depressive disorder and 18.1% and 28.8%% for anxiety disorders, compared with 0.6% and 1.0% for bipolar I, 0.8% and 1.1% for bipolar II, 1.4% and 2.4% for sub-threshold bipolar, and 1% for schizophrenia. (Depression, in particular, is one of the leading causes of disability in the U.S. and worldwide.)

b) No one in the history of mankind has told a schizophrenic to “just get over it.” There is stigma against people with schizophrenia or untreated bipolar—they are maligned as dangerous or unstable—but this is a different stigma than the one described in the anti-stigma comics.

c) Schizophrenia and other mental illnesses are virulent partially because they cause depression and anxiety. If auditory hallucinations didn’t degrade or threaten you, but instead complimented your fashion sense and occasionally remarked on the weather, schizophrenia wouldn’t be so awful. If Talking About Mental Health can alleviate depression and anxiety, then it’s going to help people of any diagnosis. ↩︎And indeed, there’s evidence that individuals perceive stigma against mental illness to be more prevalent than it actually is. ↩︎

Although men are less likely to seek treatment (here, here) for mental health conditions and are thus under-diagnosed for depression. Depression may also be masked by drug and alcohol abuse, which is more prevalent in men than women. Suicidal thoughts seem to be slightly more common in women: according to this study, 3.9% vs. 3.5%. However, although women attempt suicide more often, men are much more likely to finish the job: “Of the reported suicides in the 10 to 24 age group, 81% of the deaths were males and 19% were females. (CDC)”

Presumably this is because men use more lethal methods (hanging, carbon-monoxide poisoning, firearms) than women (self-poisoning/overdose), which may be related to gender expectations. ↩︎Buzzfeed has shareable listicles for every identity marker. For depression, they have: “21 Things Nobody Tells You About Being Depressed” “21 Comics That Capture The Frustrations Of Depression” “22 Honest Confessions From People Struggling With Depression” “15 Things You Shouldn’t Say To Someone With Depression” “This Is What Depression Really Looks Like” “What People With Depression Want You To Know” ↩︎

Since it’s legally-iffy to discharge someone who is actively suicidal, homeless people often report suicidality in the hopes of getting a bed for the night. Drunks threaten suicide and then ask for lunch, opiate addicts threaten suicide if you won’t help them detox, and one colorful BDSM aficionado “overdoses” on Motrin, gets placed in a guarded room, tries to escape, gets tackled by security, and orgasms, loudly. ↩︎