Utilitarianism Vs. Justice

June 26, 2016

The classic set-up: a #superrichkid in pastel board shorts downs a fifth of Cristal, starts up his dad’s Jaguar, and delivers ½ mv^2 to a trio of Girl Scouts. Sentence: six months in a rehab center that used to be a Hyatt. Clickbait vultures catch the scent, compare/contrast to an economically disadvantaged African-American who’s serving a decade in the Gulag for smoking a joint before his dialysis appointment.

Conclusion: the American justice system is racist, classist, and ableist.

And I agree: the American justice system probably is racist, classist, and ableist. But there’s a more insidious—and harder to solve—problem. Hard problems are rarely the result of malice or even stupidity. They are the result of ordinary people doing what they are told.

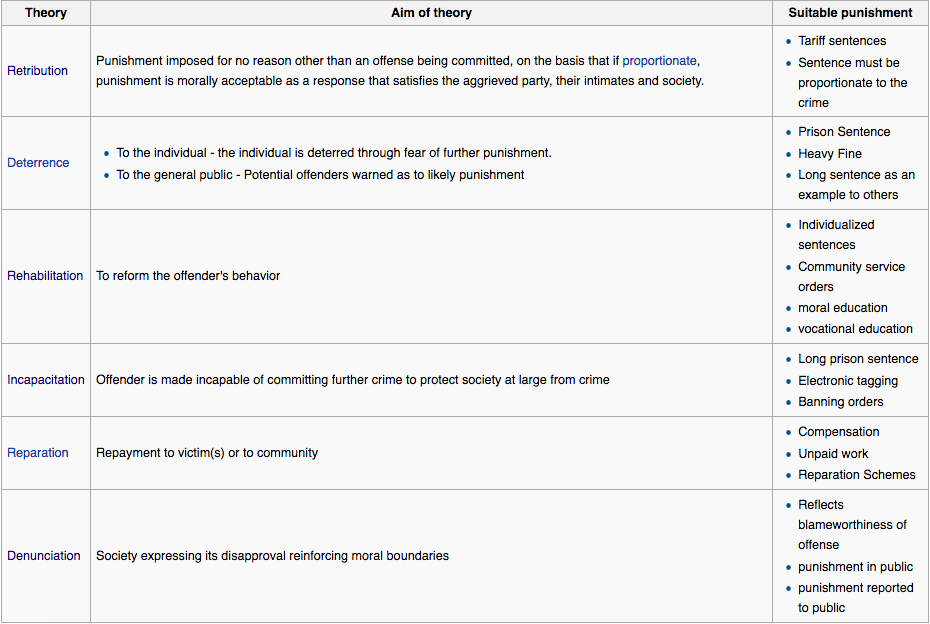

So. What are judges told to consider during sentencing?

These theories of sentencing can be divided into utilitarian and deontological.

- Retribution and Denunciation are deontological. Imprisoning a 94-year-old ex-Auschwitz guard is unlikely to deter future Nazis and comes too late to reform behavior or prevent harm. Perhaps his punishment will provide slight comfort to the families of Holocaust victims (reparation), but this is not the primary motivation for his sentence. “Some things are just wrong.”

- Incapacitation is utilitarian. Consider a Hannibal Lecter-type who is perfectly content to remain in jail and make small talk with Clarice. Assuming torture and execution are unconscionable, Dr. Lecter cannot be meaningfully punished; nevertheless, his imprisonment protects society, improving sum utility.

- Reparation depends on the ability of the criminal to make amends. If reparation was the sole basis for sentencing, a severely disabled criminal—one totally unable to recompense society—would get off scot free. Utilitarian.

- Deterrence depends on the ability of (+ need for) the public to be deterred, e.g. “making an example of him.” Utilitarian.

- And Rehabilitation depends on a criminal’s capacity for redemption. Once again, punishment is context-dependent—how will this benefit the overall good?—rather than intrinsic to the crime committed. Sorting Hat says utilitarian.

Sophisticated people like to talk smack about the Levitical ugliness of retributive justice. Punishment for punishment’s sake is barbaric. Shouldn’t our justice system try to heal society instead of inflicting new wounds?

Maybe. Maybe not.

Imagine two young men found guilty of the same offense, say, drug possession with intent to distribute. One comes from money and goes to Princeton. The other defendant has multiple incarcerated relatives and lives in the poverty of North Philadelphia.

The judge, who has a very broad jurisdiction, is an impartial race-blinded robo-utilitarian. To whom will he give the harsher sentence?

First, observe that the rationale for drug prohibition is utilitarian. The justice system cares little about marijuana possession in and of itself. Rather, it uses marijuana possession as a screening tool to find people who are at risk of committing more serious crimes in the future.

(Whether marijuana is a useful predictor and whether these rehab/deterrence techniques are worth the cost is, obviously, a matter of debate.)

But the screening tool isn’t marijuana possession, exactly: it’s getting caught. My alma mater provided a hedge-obscured courtyard a half-block from the dorms, complete with picnic table and benches, so that sulky ex-prodigies could play Hal Incandenza without risking detention. It made sense: freshmen who limited their vice to nighttime in the designated area were (probably) responsible enough to pass their classes, so the university had no reason—and did not wish—to intervene. On the other hand, students who smoked in their dorm rooms or between lectures were (probably) cavalier about their drug use and in danger of slipping up: hence RAs, hence campus police.

If poverty has forced you to room with two aunts and three asthmatic cousins, smoking indoors is probably a no-go, and safe outdoor smoking areas do not exist. But this increased likelihood of getting caught is a “““feature”””, not a bug, because low socioeconomic status (and correspondingly, minority race) is an additional risk factor for a variety of criminal offenses.

If the justice system wants to cost-effectively Minority Report future criminals, it should target the disenfranchised for arrest, and it should sentence them more harshly as well. The Princeton student has few criminal peers, no family history of crime, and plenty of social and financial support for his beachside recovery. His likelihood of recidivism is low. The Philly resident is surrounded by crime. His family cannot pay for rehab or therapy. His likelihood of recidivism is higher.

“It makes sense to spend government resources on the guy who needs it,” the argument goes. “Get him into treatment he wouldn’t otherwise be able to afford. Send a message: shape up or else. And, if worst comes to worst—keep a potentially dangerous person off the street.”

And so, for the same crime, utilitarianism disproportionately punishes the less fortunate.

One can remain a utilitarian but condemn the way utility is calculated. Perhaps prison is so harmful and rehab so ineffective that, for minor crimes, sentencing is worse than doing nothing. Reasonable, but this does not invalidate divergent sentencing for more serious crimes.

Or perhaps the awareness of injustice, “the courts hate ___ people”, causes public distrust that outweighs any benefit from utility-conscious sentencing. This argument is impossible to resolve, since the harm of “public distrust” cannot be quantified. However, choosing sentences to fit public opinion seems a perilous game, especially since the public bites onto whatever tribal narrative the media is currently selling.

Reality is rarely so simple. Let us return to our original case of affluenza-induced vehicular manslaughter, and translate the typical defense:

“The defendant made a mistake. The trial and media hoopla have been a nightmare, more than sufficient deterrence. The defendant has been enrolled in an intensive rehabilitation program, where he is learning to cope with his depression without resorting to substance abuse. He has no past history of similar offenses. He is never going to make this mistake again.”

“I understand that you want to send a message, to punish someone who has recklessly squandered his good fortune, to show that no one is above the law. But this sentence will not undo the harm that has been done. It will not prevent further harm. Does your thirst for vengeance warrant needlessly ruining a life?”

There’s something to be said for this argument, even though it is antithetical to justice. I do not claim that utilitarianism is worthless. My point is that it comes at a price.