The Stanford Marshmallow Prison Experiment

March 11, 2015

i waited 75 years and all i got was this lousy t-shirt

(trigger warnings: race, intelligence, anorexia, economics, secondary sources)

I.

When I was four, my mom had me trial the Stanford Marshmallow Experiment. You may have heard of it. From Wikipedia:

The Stanford marshmallow experiment was a series of studies on delayed gratification in the late 1960s and early 1970s led by psychologist Walter Mischel, then a professor at Stanford University. In these studies, a child was offered a choice between one small reward provided immediately or two small rewards if they waited for a short period, approximately 15 minutes, during which the tester left the room and then returned. In follow-up studies, the researchers found that children who were able to wait longer for the preferred rewards tended to have better life outcomes, as measured by SAT scores, educational attainment, body mass index (BMI), and other life measures.

My mom, who had read every child psychology book in the game, brought me to a quiet room, sat me down at a desk, and placed a lone marshmallow on a plate in front of me. She told me that I could eat the mallow immediately or I could wait fifteen minutes and receive another. She left the room and watched from a window outside.

According to Dr. Mischel, there is tremendous variety in how children distract themselves from temptation. Some children “cover their eyes with their hands or turn around so that they can’t see the tray, others start kicking the desk, or tug on their pigtails, or stroke the marshmallow as if it were a tiny stuffed animal.” A few “can be brilliantly imaginative about distracting themselves, turning their toes into piano keyboards, singing little songs, exploring their nasal orifices.”

My mom says that when I took the Stanford Marshmallow Experiment I sat in my assigned chair, staring at the treat, not playing and not moving, for the fifteen minutes until she returned.

The experiment is often touted as a test for “delayed gratification” or “willpower.” In an interview with The Atlantic, Dr. Mischel is hesitant to endorse this interpretation.

Q: Could waiting be a sign of wanting to please an adult and not a proxy for innate willpower? Presumably, even little kids can glean what the researchers want from them.

Mischel: Maybe. They might be responding to anything under the sun.

I’m not convinced that the Stanford Marshmallow Experiment tests for anything even remotely resembling “innate willpower,” because waiting fifteen minutes for a single marshmallow is a stupid thing to do. The opportunity cost of wasting fifteen minutes is way greater than the utility of one marshmallow. My mom has a sweet tooth—it’s not like the marshmallow was a rare treat in my otherwise Dickensian life—and I’m more of a Reese’s peanut butter cup guy anyway. From The Atlantic:

Mischel: …in the studies we did, the marshmallows are not the ones presented in the media and on YouTube or on the cover of my book. They were these teeny, weeny pathetic miniature marshmallows or the difference between one tiny, little pretzel stick and two little pretzel sticks, less than an inch tall. It’s really not about candy. Many of the kids would bag their little treats to say, “Look what I did and how proud mom is going to be.”

You could have all the willpower in the world and still decide that you don’t want to wait around for a pretzel stick. Conversely, the experiment could have lacked any tangible reward and some kids still would have waited.

That said, if the experiment predicts SAT scores then it’s clearly testing for something. It’s hard to tease out what that something is. Perhaps the delayed-gratifiers want to impress authority figures, perhaps they recognize the challenge and have some internal desire for achievement, perhaps they are simply used to doing as they are told. I’m going to sum all these motivations into The Desire To Pass Tests [1]. And it makes intuitive sense that TDTPT would predict SAT scores and number of degrees, because these are cultural tests of intelligence. It makes sense that TDTPT would predict BMI, because this is a cultural test of appearance. It makes sense that "preschool children who delayed gratification longer in the self-imposed delay paradigm were described more than 10 years later by their parents as adolescents who were significantly more competent,“ because parental approval is the oldest and most universal test there is.

All of these seem like good things.

But I think there’s something ominous about a kid so eager-to-please that he sits perfectly still for fifteen minutes waiting for a marshmallow.

II.

What predicts TDTPT? From Wikipedia:

The [Stanford Marshmallow] experiment has its roots in an earlier one performed in Trinidad, where Mischel noticed that the different ethnic groups living on the island had contrasting stereotypes about one another, specifically the other’s perceived recklessness, self-control, and ability to have fun. This small (n= 53) study focused on male and female children aged 7 to 9 (35 Black and 18 East Indian) in a rural Trinidad school. The children were required to indicate a choice between receiving a 1¢ candy immediately, or having a (preferable) 10¢ candy given to them in one week’s time. Mischel reported a significant ethnic difference, large age differences, and that "Comparison of the “high” versus “low” socioeconomic groups on the experimental choice did not yield a significant difference”. Absence of the father was prevalent in the African-descent group (occurring only once in the East Indian group), and this variable showed the strongest link to delay of gratification, with children from intact families showing superior ability to delay.

A study with n=53 wouldn’t be worth talking about, except that other tests show similar ethnic differences. From a Washington Post article on the SAT:

The third chart shows that Asians and whites get much higher scores than other ethnic groups. Asians top the test with an average score of 1,645, while African Americans record the lowest score with an average of 1,278. It appears that the advantage of white students over black and Hispanic students is roughly similar for the reading, math and writing test.

And, most controversially:

The connection between race and intelligence has been a subject of debate in both popular science and academic testing since the inception of IQ testing in the early 20th century. The debate concerns the interpretation of research findings that American test takers identifying as “White” tend on average to score higher than test takers of African ancestry on IQ tests, and subsequent findings that test takers of East Asian background tend to score higher than whites. (Wikipedia)

(It’s hard to find hard data on race-IQ correlations except from scary-biased websites. This is the best I could do.)

Before you freak out, let me make three important thesis statements.

1. IQ tests are a weak measure of “innate intelligence.”

2. There’s no evidence that race has anything to do with intelligence.

3. This is about taking tests.

Okay? Let’s continue.

IQ has some degree of genetic heritability: the agreed-upon number tends to be around 0.5. (i.e. 50% of the difference in IQ between individuals can be explained by genes.)

Scores on the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children were analyzed in a sample of 7-year-old twins from the National Collaborative Perinatal Project. A substantial proportion of the twins were raised in families living near or below the poverty level. Biometric analyses were conducted using models allowing for components attributable to the additive effects of genotype, shared environment, and non-shared environment to interact with socioeconomic status (SES) measured as a continuous variable. Results demonstrate that the proportions of IQ variance attributable to genes and environment vary nonlinearly with SES. The models suggest that in impoverished families, 60% of the variance in IQ is accounted for by the shared environment, and the contribution of genes is close to zero; in affluent families, the result is almost exactly the reverse.

A similar trend is seen globally: the least developed countries, with the most poverty, starvation, and infectious disease, tend to have lower IQ scores, presumably because IQ test study sessions are somewhat hindered by having schistosomiasis.

“But you can’t study for an IQ test!” That’s what they said about the SAT, too.

Unlike existing academic exams, it [the SAT] was intended to measure innate ability—not what a student had learned but what a student was capable of learning—and it stated clearly in the instructions that “cramming or last-minute reviewing” was pointless.

Although the College Board still maintains that preparatory courses have little-if-any benefit, some outside studies argue for much greater value, Furthermore, income correlates with SAT score and retaking the test improves scores more often than not, so it is extremely likely that extracurricular education has a significant effect, i.e. the test is “coachable.”

All right, so (according to Google) here’s a past SAT question:

BIRD : NEST ::

a) dog : doghouse

b) squirrel : tree

c) beaver : dam

d) cat : litter box

e) book : library

And (according to Google) here’s a question off the Stanford-Binet V IQ test:

BROTHER IS TO SISTER AS NIECE IS TO:

a) Mother

b) Daughter

c) Aunt

d) Uncle

e) Nephew

Huh.

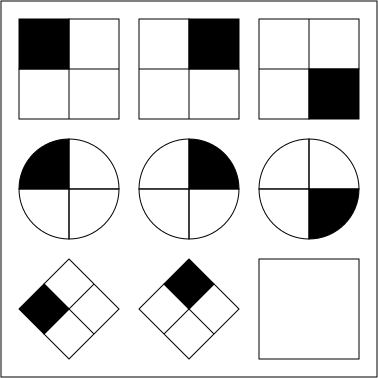

The “verbal analogies” section of the SAT has since been removed; furthermore, actual IQ test questions are kept in a vault somewhere, so I can’t promise that these examples are 100% accurate. My argument isn’t that SAT and IQ tests are exactly the same, though: my argument is that they are both coachable. All IQ verbal reasoning questions look like something from Professor Layton. You can get better at Professor Layton. “What about the nonverbal pattern recognition IQ tests? You can’t train for that." Raven’s Progressive Matrices is a language-independent test in which the subject must identify the missing element that completes a pattern. Here’s what a sample Raven’s problem looks like:

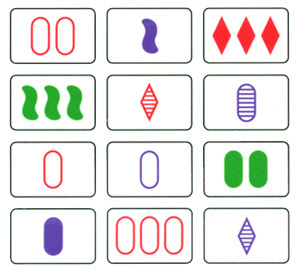

Can you figure out what goes in the blank square? Okay, here’s what the card game Set looks like:

The object of Set (which is a great game) is to find three cards that fulfill all of the following conditions:

-

They all have the same number, or they have three different numbers.

-

They all have the same symbol, or they have three different symbols.

-

They all have the same shading, or they have three different shadings.

-

They all have the same color, or they have three different colors.

i.e. pattern recognition, i.e. this is literally an IQ test_._ And you can get better at Set. My mom bought the game for me—she saw it advertised in The New Yorker—when I was six or seven years old. I was okay at it. We played it a lot. By ten, I was the indomitable King of Sets, a glorious reign that lasted until a friend dedicated six months to Set practice and proceeded to kick my ass. The King is dead, long live the King.

My point being that even though kids don’t take IQ Test Prep courses (for the most part), that doesn’t mean they’re not trained to test. Check out the racial differences in IQ and SAT scores—for both tests, scores are East Asians > Whites > Hispanics > Blacks. Coincidence? Evidence of a genetic basis for intelligence?

From The New Yorker:

The black-white gap, he pointed out, differs dramatically by age. He noted that the tests we have for measuring the cognitive functioning of infants, though admittedly crude, show the races to be almost the same. By age four, the average black I.Q. is 95.4—only four and a half points behind the average white I.Q. Then the real gap emerges: from age four through twenty-four, blacks lose six-tenths of a point a year, until their scores settle at 83.4.

And:

If I.Q. is innate, it shouldn’t make a difference whether it’s a mixed-race child’s mother or father who is black. But it does: children with a white mother and a black father have an eight-point I.Q. advantage over those with a black mother and a white father. And it shouldn’t make much of a difference where a mixed-race child is born. But, again, it does: the children fathered by black American G.I.s in postwar Germany and brought up by their German mothers have the same I.Q.s as the children of white American G.I.s and German mothers.

I think that’s pretty much a slam dunk. This is not about race. This is about culture [2]. It makes sense that racial differences are much more pronounced on the SAT than the IQ: the effects of environment and nurture are cumulative over time. Question is, why do people of certain cultures do better on tests? Perhaps the content of the test is discriminatory—certain questions might require cultural knowledge that is more common among wealthy whites. Except:

- Whatever cultural bias the tests have would have to favor Asians even more than it favors whites.

- IQ tests predict future achievement just as well for black and white Americans.

- Similar black-white score gaps exist for tests that are completely nonverbal, such as the Raven’s.

A more promising explanation is stereotype threat:

If negative stereotypes are present regarding a specific group, group members are likely to become anxious about their performance, which may hinder their ability to perform at their maximum level. For example, stereotype threat can lower the intellectual performance of African-Americans taking the SAT reasoning test used for college entrance in the United States…

Which has some support. For example:

In two threat conditions, participants received either standard APM [a variation of the Raven’s] instructions (standard threat) or were told that the APM was an IQ test (high threat). In a low threat condition, participants were told that the APM was a set of puzzles and that the researchers wanted their opinions of them…Although African American participants underperformed Whites under both standard and high threat instructions, they performed just as well as Whites did under low threat instructions.

Some studies have also proposed the idea of "stereotype boost,” arguing that being aware of positive stereotypes can improve test-taking performance. But as tempting as these explanations are, there are serious concerns for publication bias in this field of research, not to mention controversy over the strength of these stereotype effects, with some scholars arguing that they explain all of the test score race gap (by the evidence, unlikely) or none of it (maybe) or something in between (probably).

Here’s what I think.

I had fun taking my IQ test. I was anxious, sure—the examiner was a lady with glasses and her hair in a bun, and that meant performance—but it was a good anxiety, an alertness, an adrenaline rush, a taut strength. I was prepared for this test. I was six years old, going on seven, and I was every teacher’s favorite student. My mom did logic puzzles with me on the car ride over. I recall that the examiner complimented my vocabulary. I remember that she smiled a lot.

I did very well on my IQ test.

Afterwards, my mom contacted a Profoundly Gifted Institute advocating for kids with IQs in the 99.9th percentile [3]. The institute recommended that I start homeschooling, and so I got to pick out a personalized curriculum, and so I liked learning, and so I got good grades, and so on, and so forth. I took a thousand multiple-choice tests and learned the meta-knowledge of how to take them. From age 10 to 13, I tested out of most of my required high school courses. When my friends said I was a “genius,” I would sort-of-joke that I didn’t know anything but could score 75% on any test with a Scantron.

Good things lead to good things, bad things lead to bad things: small differences grow and metastasize over time. Stereotype threat isn’t an acute process, it’s a chronic one. Some cultures (Asian-Americans, upper-middle-class white people) inculcate their children with test-taking ability, both the practical side (i.e., Scantron savvy, playing Sets) and the psychological side (The Desire To Pass Tests). Other cultures, less so. This small early childhood gap becomes exponentially larger as “gifted” children are praised and offered trips to the Natural History Museum and “average” children decide to stop caring and just eat the goddamn marshmallow.

It is this Test Taking Ability that, in large part, predicts the results of the Stanford Marshmallow Experiment, IQ testing, the SAT, and “other life measures.”

The most extreme interpretation of TTA is that IQ-type tests have nothing at all do with “intelligence”: doing well on a test predicts success on future tests, being good at logic puzzles means that you are good at logic puzzles. I am not an extremist, and I do think that IQ has real meaning. A person with an IQ of 140 is probably more “innately intelligent” than someone with an IQ of 100, at least with regards to the “quantitative reasoning, visual-spatial processing, and working memory” skills that are tested, and this type of intelligence probably does have something to do with success as an economist or biochemist or whatever. SAT scores are less innate than IQ, but even so, someone with a perfect math SAT will probably have a brighter future in math-associated fields than someone with a subpar score [4]. I am not saying tests are useless—I am saying that they have far more Test Taking Ability noise to intelligence signal than most people will admit, and that this noise is more than enough to explain racial score disparities [5]. The map is not the territory.

(Sort of a tangent, but I think this is the strongest argument for affirmative action. Affirmative action is used to compensate for a known bias: some groups of people will not do as well on tests, despite being just as or more competent. Example: suppose that on a given test black doctors average ten points lower than equal-competency (as measured by, say, patient outcomes) white doctors. Suppose that aside from this bias the test is an excellent predictor of physician ability. This implies that a black doctor who scores five points lower than his white colleague is probably more competent, despite having a lower score [6].)

And so the other point I want to make is that discrimination can occur without anyone actually being racist. IQ tests are not racist. The SAT is not racist. The people ordering/designing/giving the tests aren’t racist. The parents of underachieving kids aren’t racist or even doing anything “wrong”: presumably, these parents are skeptical of the Arbitrary Tests of a culture that, historically, has treated them a little poorly.

No one is at fault, but it is possible for a system to have terrible consequences even when every individual within the system has good intentions. After all, resources are finite. Jobs are limited. If you won’t study for an arbitrary and annoying standardized test, someone else will. The show must go on. Have fun with unemployment.

III.

It’s hard to become a doctor.

Medical school applicants are expected to pass a (relatively) rigorous undergraduate curriculum with consistently high grades: the average applicant GPA is 3.54. They are expected to score well on the MCAT, a five hour exam that, besides the Putnam, is widely considered to be the hardest pre-doctorate standardized test. The current MCAT is ranked on a 3-45 scale: the average score is a 24, the average score of a medical school applicant is 29, and the average score of a medical school matriculant is 31, i.e. most people fail. In 2015, the MCAT will add three new topics and stretch out to seven hours long. It is expected to become much more difficult.

Medical school applicants are expected to have separate Clinical, Research and Community Service experiences, preferably each supported by letters of recommendation. Applicants must detail these experiences in their personal statement, in the Most Meaningful Experiences section of their Primary Application, at various points throughout their Secondary Application, and then once again during one-on-one school interviews. Applicants should sound passionate but not maudlin; they should admit flaws but also show how they have worked to overcome these flaws; they should sound confident in their knowledge but also humbled by how much there is to know. They must pass tests of fire, ice, and lightning. They must defeat a current medical student in martial combat. They must not have party photos on Facebook. They must wear formal attire.

Between transcript fees, primary application fees, secondary application fees, and travel costs, the medical school application process alone tends to cost three to four-thousand dollars. School tuition differs from public to private schools, but averages between forty and fifty-thousand dollars per year. The median indebtedness at time of graduation is $175,000, but horror stories of compound interest and total repayments of $500,000 or $600,000 abound. Moreover, medical school tuition is rising, physician income has barely kept pace with inflation, reimbursement is likely to decrease with the ACA, and this is a problem that is likely to get worse, not better.

Doctors still make good money, of course, and most pre-meds don’t go into medicine for the cash. However:

Surveys find consistently low levels of physician job satisfaction (although this varies by specialty), with burnout rates significantly above those of the general population [7]. In a 2012 survey of 13,575 physicians:

-

Over 84 percent of physicians agree that the medical profession is in decline.

-

The majority of physicians – 57.9 percent – would not recommend medicine as a career to their children or other young people.

-

Over 60 percent of physicians would retire today if they had the means.

(I will also point out of evidence of disproportionately high divorce and suicide rates among physicians, although the latter could be an artifact of access to prescription drugs and how-to-kill-yourself know-how.)

And so the punchline to all this is:

Washington, D.C., October 29, 2014—The number of students who enrolled in the nation’s medical schools for the first time in 2014 has reached a new high, totaling 20,343, according to data released today by the AAMC (Association of American Medical Colleges). The total number of applicants to medical school also rose by 3.1 percent, to a record 49,480. First-time applicants—an important indicator of interest in medicine—increased by 2.7 percent to 36,697. (AAMC)

Despite the increasing costs and opportunity costs of medical school, and despite the widespread pessimism of practicing physicians, more people than ever want to become doctors. Why?

Switch tracks for a moment. It’s expensive to go to college.

The cost of higher education has jumped more than 13-fold in records dating to 1978, illustrating bloated tuition costs even as enrollment slows and graduates struggle to land jobs. (Bloomberg)

Recent data from 2010 to 2011 have shown that tuition and fees rose by 4.5% at private colleges and more than 8% at public institutions. Not only do these numbers mean that the sticker price of higher education is far outpacing inflation rate and affordability, but it also means that tuition has grown almost 500% since 1986. (Wikipedia)

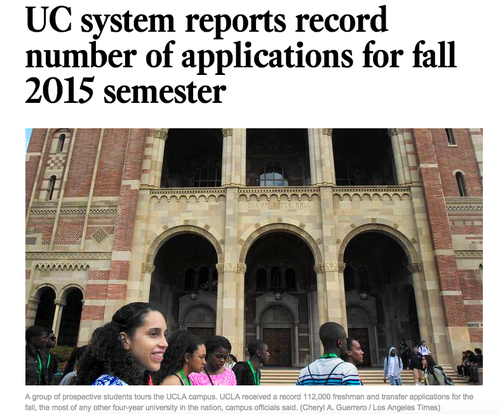

I’m most familiar with the University of California system. In 2009:

As the University of California’s Board of Regents met Thursday at U.C.L.A. and approved a plan to raise undergraduate fees — the equivalent of tuition — 32 percent next fall, hundreds of students from campuses across the state demonstrated outside, beating drums and chanting slogans against the increase. (NY Times)

And in 2014:

The UC regents voted in November to increase tuition by as much as 28% over the next five years, triggering student protests and a chorus of political bellowing, and promised to make higher education funding one of the Capitol’s hottest policy debates in the coming year. (LA Times)

If your explanation for “Why does this keep happening?” features the phrase “greedy UC administrators,” please keep in mind that greed is universal, but ramping up prices year after year is not. If Coca-Cola doubled prices, people would buy Pepsi. If the UC system raises prices:

There are no consequences whatsoever.

Part of this is rational economics: even factoring in rising tuition, the value of a four-year bachelor’s degree is, on average, near an all time high. But “average” is a loaded word. Only 60% of students graduate in four years, and taking a fifth or sixth year causes a major decrease in return on investment. Not graduating at all (about 40% of students) is even worse. And even for students who graduate on time, about a quarter of majors (e.g. psychology, zoology, drama) end up financially worse-off than high school grads.

It’s this last finding that is responsible for the most hand-wringing and society-bemoaning. As the price of college has increased, totally unprofitable majors have remained among the most popular. Why?

Switch tracks for a moment. Work sucks and you don’t get paid enough.

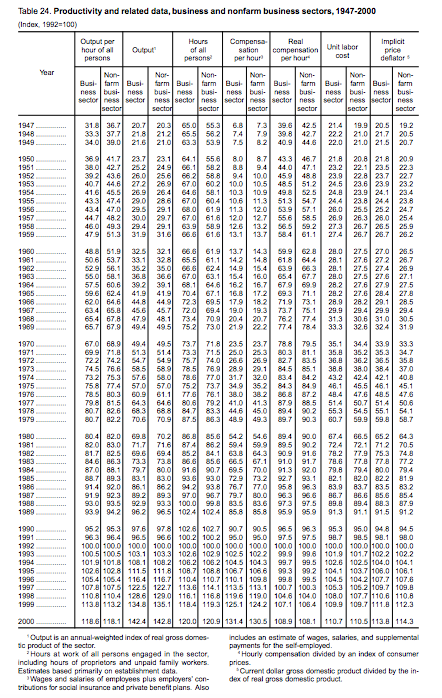

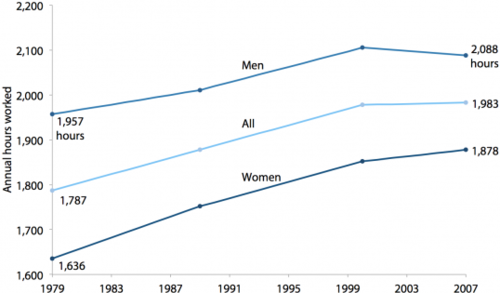

Using the above data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor, Erik Rauch calculates that, thanks to educational/technological advances, a worker today needs to work only 11 hours per week to produce as much as one working 40 hours per week in 1950. So of course, workers today work fewer hours:

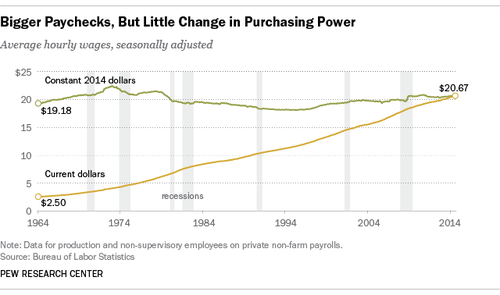

And are paid more for their work:

Haha, just kidding.

This is a third example of a situation where an investment is getting “worse"—higher opportunity cost, higher cost, and/or lower rate of return—and yet more people than ever want to invest. Why?

- A situation in which the demand for a product does not increase or decrease correspondingly with a fall or rise in its price. From the supplier’s viewpoint, this is a highly desirable situation because price and total revenue are directly related; an increase in price increases total revenue despite a fall in the quantity demanded.

The demand elasticity of college tuition has been estimated at -0.10, i.e. for every 1% change in tuition, enrollment will drop by a tenth of a percent. That’s pretty inelastic, and I suspect that for upper-middle class and upper class families tuition elasticity is near zero: going to college is not a debate, even if you’re going to major in Sociology. If all the colleges in the United States doubled their tuition, would they still fill their classrooms? Yes. This has already happened. Medical school is perhaps even more inelastic: being a doctor is a privilege for which some people will pay any price. If medical schools doubled tuition and physician income scarcely changed, would the practice still attract hordes of ambitious pre-meds? Already happened. Similarly, if medical schools increased the opportunity cost of attendance, i.e. increasing the GPA, MCAT, and extracurricular requirements, would students still apply in droves? Already happened [8].

How inelastic is the global job market [9]? Ask the Honduran workers making t-shirts for $13 a day because they have no better option. It’s no fun to be underpaid, but it’s better than not being paid at all. Between outsourced jobs and computerization, competition for U.S. jobs has increased dramatically. Earlier, I said that the value of a bachelor’s degree is near an all-time high; however, underemployment (think "Sartre working at Starbucks”) of recent graduates has increased significantly over the past two decades. How can these both be true?

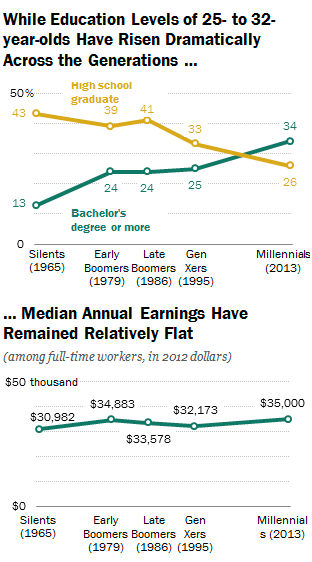

While earnings of those with a college degree rose, the typical high school graduate’s earnings fell by more than $3,000, from $31,384 in 1965 to $28,000 in 2013. (Pew Research Center)

…the unemployment rate for Millennials with a college degree is more than double the rate for college-educated Silents in 1965 (3.8% vs. 1.4%). But the unemployment rate for Millennials with only a high school diploma is even higher: 12.2%, or more than 8 percentage points more than for college graduates and almost triple the unemployment rate of Silents with a high school diploma in 1965. (Pew)

As a result, the value of a college degree has remained high over the past decade in large part because of the declining fortunes of those without one. Thus, while the challenges recent graduates have faced in finding a good job might mean that that a college degree will not be as lucrative as it once was, having one is likely to remain better than the alternative. (New York Fed)

This is a terrifying result. College is a worthwhile investment because the prospects of people with only a high-school diploma are really, really bleak. Take a look at this graph:

Societal education has had almost no effect on income: it has been absorbed into the system and has become a requirement. This is capitalism’s take on the Red Queen Hypothesis:

Now, here, you see, it takes all the running you can do, to keep in the same place.

And so I have one last rhetorical question on this topic. If competition continues to increase—and it seems likely that it will—what type of person will it favor? Who will score well in every class and on the SAT and on the MCAT and graduate college in four years, summa cum laude? Who will gain Clinical and Research and Community Service experiences and acquire Strong Letters of Recommendation and sound passionate but not maudlin and admit flaws but show how they have worked to overcome these flaws and sound confident in their knowledge but humbled by how much there is to know? Who will climb every mountain without hesitation, no matter how high the ascent or meager the rewards? Who has such discipline, such patience, such ambition?

IV.

MTV CONFESSION CAM: I was an accidental anorexic.

I was 17 years old when I moved into the college dorms and decided that I wanted a six-pack. I had never thought about my body too much before that—I didn’t play sports, I didn’t care about fashion, and I spent most of my time daydreaming about fantasy novels and videogames. In the dorms, however, I finally realized that girls existed. I wasn’t sure about how to get a girlfriend on purpose, but I was pretty sure it had something to do with “abs.” So I decided to work on that.

I began running for 45 minutes three times a week, along with daily stretching, push-ups, and crunches. After hearing a fire-and-brimstone “Talk About Nutrition!” presentation in the dining commons, I decided that I would have to change my diet as well. I stopped eating sweets of any sort. Increased lean protein intake. All breaded objects became whole wheat. But this didn’t seem enough. Food, I decided, was an ephemeral pleasure, whereas a well-sculpted body was a constant joy to live in and behold. Why bother with anything but the healthiest of foods? After some trial and error, I decided upon the optimal meal plan.

Breakfast: Oatmeal, one orange, one kiwi.

Lunch: Salad (lettuce with kidney & garbanzo beans), PB&J, hardboiled egg.

Snack: Orange.

Dinner: Cheerios and milk, salad, orange.

I was proud of my discipline, and the nights when I went to sleep hungry only intensified my pride, as I first ignored and then began to appreciate the sharp jabs of an empty stomach. I was no longer getting fit to attract girls—I was getting fit for me. After a month of running, my progress seemed to flatline. I added weights to my regimen. I wasn’t sure how many reps to do, so I decided to just lift until my arms went limp. After another month, I had developed only mild abdominal definition. I decided to step it up: 200 push-ups upon waking every day, stretches and crunches in the evening. I wasn’t perfect. Sometimes I would give in to temptation and eat something off-diet—if someone took me out to lunch, or if I had a cookie at a school event—and I would feel guilty and sad for a while, but before long I would regain my composure and vow to increase my exercise regimen in the next few days to make up for my setback.

After three months, I went home for winter break. My mom said that I looked like an Auschwitz survivor. I said that was a huge overreaction. I asked my dad what he thought. My dad said that I looked a little skinny but that there was nothing wrong with getting into shape. I went back to school and kept up my routine. My strength declined. I wasn’t sure why. My ribs could be individually grasped. I visited home and weighed myself at 107 pounds.

“That’s really low,” my mom said.

“It’s not that bad,” I said.

My mom convinced me to go to the campus nutritionist. The nutritionist, who was middle-aged, and blonde, and wore glasses, and smiled a lot, told me that I had lost 35 pounds in four and half months, and that remaining at this weight could be dangerous.

“I was just trying to be fit,” I explained to her.

“Your current weight isn’t fit,” she said. “It’s not healthy.”

“I really don’t want to be fat,” I said.

“You’re not going to be fat,” she said. “That’s not your body type.”

“I guess. I didn’t mean to. I was just trying to eat healthy.”

“Right now, you can eat whatever you want,” she said. “You need to gain some weight. Back into the 140s, at least.”

“I’m never sure what to eat. I don’t want to eat too much.”

“I’ll help you come up with a meal plan,” she said. “We can figure out what you need to do.”

I felt tremendous relief. This was a test I could pass.

V.

It does not surprise me that anorexia is significantly more common among teenagers with better grades and higher parental education. It does not surprise me because The Desire To Pass Tests associated with anorexia and The Desire To Pass Tests that made me a grade-school rockstar felt exactly the same. I never hated my body, I just thought I could do better. I just didn’t want to mess up.

I’m not claiming that everyone with TDTPT has anorexia, obviously. I’m arguing the converse: I think everyone with anorexia has TDTPT.

Recently, I’ve been tutoring 30 or so pre-med students. These students—mostly Asian, some white—are smart and motivated. They have done cross-country, rowing, and tennis. They play piano, violin, and cello. They have Clinical, Research, and Community Service experience. And, in certain consistent ways, they are unhappy. They are anxious and self-doubting. They crave reassurance. They downplay successes. They feel that all my compliments are “just being nice.” They radiate fatigue:

“So, what do you do when you’re not doing medical stuff?” I asked one of them.

“I don’t know. I play videogames sometimes. Except I should probably quit.”

“What are you going to do instead?”

“I don’t know,” he said. “Study more, I guess.”

“Your grades are pretty good, though.”

“For medical school? They’re, at best, a little below average.”

And he wasn’t wrong.

I think the psychopathology term for TDTPT is “perfectionism.”

Perfectionists strain compulsively and unceasingly toward unobtainable goals, and measure their self-worth by productivity and accomplishment. Pressuring oneself to achieve unrealistic goals inevitably sets the person up for disappointment. Perfectionists tend to be harsh critics of themselves when they fail to meet their standards. (Wikipedia)

Perfectionism correlates with giftedness and academic success. It also:

…is a risk factor for obsessive compulsive disorder, obsessive compulsive personality disorder, eating disorders, social anxiety, social phobia, body dysmorphic disorder, workaholism, self harm, substance abuse, and clinical depression as well as physical problems like chronic stress, and heart disease. In addition, studies have found that people with perfectionism have a higher mortality rate than those without perfectionism.

The obvious question, then: why is perfectionism helpful for some people and horribly distressing for others? In lieu of an answer, mainstream psychology has provided a fuckfest of semantic debate [10]. Much of the pertinent literature draws a distinction between “adaptive” perfectionism and “maladaptive” perfectionism: the former is characterized by “high personal standards but low distress when the standards are not met” whereas maladaptive perfectionists have “high personal standards and high distress,” and non-perfectionists just have low standards. Shockingly, research shows:

Path models revealed that adaptive perfectionism was positively associated with self-esteem and maladaptive perfectionism was negatively associated with self-esteem. (Here)

Further, adaptive perfectionists reported significantly higher satisfaction across many life domains for both groups than maladaptive perfectionists and non-perfectionists. (Here)

So maladaptive perfectionism correlates with low self-esteem—what is maladaptive perfectionism, again? “Perfectionists who feel inadequate for not meeting personal standards.” Isn’t feeling “inadequate for not meeting personal standards” the definition of low self-esteem? This is circular reasoning—the maladaptive/adaptive dichotomy doesn’t explain anything, all it says is that perfectionism is “maladaptive” when it’s not working for you and “adaptive” when it is.

Attempt #2 to explain why perfectionism has mixed effects is to split it into “socially prescribed” and “self-oriented” perfectionism, where socially prescribed perfectionism is extrinsically motivated (“If I make a mistake, people will think I’m a failure”) and self-oriented perfectionism comes from within.

Generally, socially prescribed perfectionism had stronger associations with maladaptive constructs than did self-oriented perfectionism. In contrast to the assertion that self-oriented perfectionism is exclusively a vulnerability factor (Benson, 2003), and as hypothesized, results indicated that high self-oriented perfectionism in the absence of socially prescribed perfectionism is adaptive. (Here)

This study implies that socially prescribed –> maladaptive and self oriented –> adaptive, but it has the causality backwards. If you ace a difficult O-chem test, do you want to believe that this was the result of your übermensch willpower or “big surprise, my parents have been pushing me for years”? Inversely, if you just failed an O-chem test, it’s much preferable to think “My family thinks I’m a failure. They’re so unfair,” instead of “I’m a loser." This is Psych 101:

A self-serving bias is any cognitive or perceptual process that is distorted by the need to maintain and enhance self-esteem…For example, a student who attributes earning a good grade on an exam to their own intelligence and preparation but attributes earning a poor grade to the teacher’s poor teaching ability or unfair test questions is exhibiting the self-serving bias. Studies have shown that similar attributions are made in various situations, such as the workplace, interpersonal relationships, sports, and consumer decisions. (Wikipedia)

Being intrinsically motivated doesn’t make you successful. Feeling successful makes you intrinsically motivated.

My point is that when filling out your character sheet, you can’t dump all your points into "self-oriented adaptive super-awesome perfectionism” and steamroll through life, because this trait doesn’t exist—in fact, any personality trait reputed as solely good is about as likely as a perpetual motion machine pulled by chupacabras. Perfectionism—like literally everything else—is part of a spectrum, good in moderation and dangerous in overdose. Courtesy of Google Sheets, I bring to you:

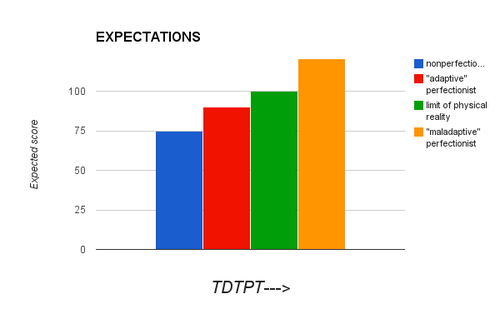

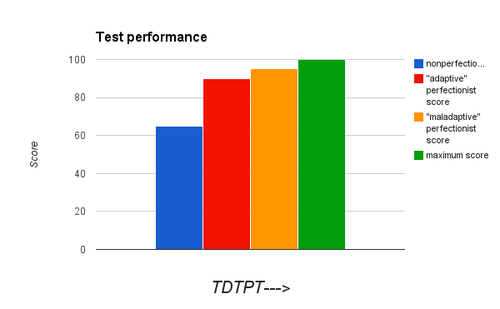

TDTPT is the underlying trait. Someone with low TDTPT, the “nonperfectionist,” who has failed for years and is—what was that quote?—"described by his parents as significantly less competent,“ has given up hope, doesn’t study, and doesn’t expect to do well, a 75, passing but just barely. Someone with high TDTPT, the "maladaptive” perfectionist, holds back tears when he gets a B+, expects to get 100 plus 30 bonus points and personal congratulations from the Founding Fathers—or, realistically, 100, and even one point less will mean failure. And a moderate TDTPT expects to get a 90. And so come test day:

The low TDTPT gets a 65, 10 points less than he expected, and feels disappointed. The moderate TDTPT gets a 90, just as planned, and feels pleased. The high TDTPT gets a 95 and is crushed. It’s about the discrepancy, man. Consider taking up Buddhism.

And so if you select for high TDTPT, if you take only the highest scores and most feverishly dedicated hoop-jumping applicants, then there is no way around it: you are selecting for a high fraction of unhappy people. Sticking with medical examples, take a look at the mental health of medical students.

More than 2,000 medical students and residents responded, for an overall response rate of 89%. Based on categorical levels from the CES-D, 12% had probable major depression and 9.2% had probable mild/moderate depression…Nearly 6% reported suicidal ideation. (Here)

According to the CDC, the point prevalence of depression in the adult general population is 5.4%. Why would medical students have a 3-4 times higher prevalence of depression? Two possibilities:

1. The coursework of medical school is harsh enough to give people clinical depression_._

2. Medical schools admit people who already tend towards depression.

The second possibility seems more likely. Neither possibility is good.

And it gets worse. There’s reason to believe that the number of high-TDTPT maladaptive perfectionists is underestimated. For one, most studies assess perfectionism via multiple choice test, such as the Almost Perfect Scale or the Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale. Thing is, perfectionists are good at taking tests_._ I instinctively give personality tests “what they want to hear” and I almost never trigger the control questions designed to catch you if you are doing this [11]. (Hint: rule out the extreme answers.) I make the MMPI look like the Myers-Briggs, and I make the Myers-Briggs look like a “Which Naruto Character Are YOU?” personality quiz. I do this without even trying, which is important because many perfectionists have poor insight—e.g., until I hit 110 pounds, I didn’t think my anorexia was unhealthy and/or neurotic; on the contrary, I was proud of my hard work. If had taken a survey at that time, there’s a good chance I wouldn’t have registered as perfectionist. It’s also worth noting that hardcore perfectionists who “measure self-worth by accomplishment” and “have a morbid fear of failure,” probably aren’t too keen on seeking out psychiatric treatment and admitting/getting diagnosed with depression, anxiety, etc.

But the greatest miscalculation of perfectionism occurs when you imagine it as something that only affects the classroom. I’ve used Scantron-centric examples because Scantrons are easy to quantify, but tests are everywhere, and I promise you that the same trait that made me check my answers ten times over is present in the girl that spends two and a half hours doing her makeup, pausing every five minutes to ask a roommate if she looks ugly. TDTPT is the source of anorexia, body dysmorphia, workaholism, anxiety (“I just can’t find anything to say that doesn’t sound stupid”), obsession, and a hundred million cases of anhedonia, fatigue, and inadequacy: that pervasive country-wide fear that I Am Not Good Enough. “Your definition seems to include a lot of people.” A lot of people watch TV. This is America—the tests start as soon as you leave the womb, they don’t stop when you die, and all along the way, everyone knows where you stand in the class ranking.

VI.

There’s a type of joke that I think of as the “white people” joke, although it’s rarely funny and it doesn’t have to be about someone who’s white. The joke is about a mid-40’s housewife who is way too well-educated and bored to be a housewife, and so she tries to find the Grail of healthy food (organic, GMO-free, low acidity, one diet after another) and she plants a garden, and she adopts pets, and she joins nonprofits, and she joins the school board, and she reads every novel on NPR’s end of the year list, and she gets weekly therapy and monthly massages (to about the same effect), and she meditates on the present, and she achieves peace with the past, and she contemplates the future, and everything is feng shui, and yet, despite all this, she feels restless, anxious, unhappy, and she dreams of some sort of vacation.

Or sometimes the joke is about an elderly businessman on his second hair transplant and third cardiac stent and twenty-billionth dollar, and his kids all have grandkids and his wife is deceased, and when he goes out he he orders scotch more expensive than houses, but that isn’t too often—he’s seen enough parties, he’s seen enough people, he has no strong affections, and he works round the clock fighting tooth-and-nail for his billions, because he’s not sure what else, exactly, he’s supposed to be doing.

Or the joke is about a magazine-cover movie actress who has the adoration of thousands and still feels worthless. Or the joke is about a virginal computer science genius who has deleted his OKCupid and decided to eschew all noncoding activities. Or the joke is about a millionaire athlete under investigation for using anabolic steroids. Or the joke is about a 50-something cardiologist who hates all his patients but knows that he’d hate being retired even more. Or the joke is about a young power couple who like each other very much, love, maybe, but they’re both distracted by the nagging feeling that they could do better, that they should be shooting for something greater, and so they break up and find new partners and the process repeats again.

And the joke, which you hear on forums or sitcoms or in crowded sports bars, goes: “Haha, even though these people are successful, they’re still dissatisfied."

And I’m here to tell you that this joke is totally backwards. It’s because these people have always been dissatisfied that they achieved success.

VII.

What will happen when the robots take over?

The combination of big data and smart machines will take over some occupations wholesale; in others it will allow firms to do more with fewer workers. Text-mining programs will displace professional jobs in legal services. Biopsies will be analysed more efficiently by image-processing software than lab technicians. Accountants may follow travel agents and tellers into the unemployment line as tax software improves. Machines are already turning basic sports results and financial data into good-enough news stories. Jobs that are not easily automated may still be transformed. New data-processing technology could break “cognitive” jobs down into smaller and smaller tasks. As well as opening the way to eventual automation this could reduce the satisfaction from such work, just as the satisfaction of making things was reduced by deskilling and interchangeable parts in the 19th century. (The Economist)

i.e, the beginning of a Godspeed You! song.

Tyler Cowen, an economist at George Mason University and a much-read blogger, writes in his most recent book, “Average is Over”, that rich economies seem to be bifurcating into a small group of workers with skills highly complementary with machine intelligence, for whom he has high hopes, and the rest, for whom not so much. (The Economist)

There will be a labor market in the service sector for non-routine tasks that can be performed interchangeably by just about anyone—and these will not pay a living wage—and there will be some new opportunities created for complex non-routine work, but the gains at this top of the labor market will not be offset by losses in the middle and gains of terrible jobs at the bottom. I’m not sure that jobs will disappear altogether, though that seems possible, but the jobs that are left will be lower paying and less secure than those that exist now. The middle is moving to the bottom. (Justin Reich, in a Pew article)

Of course, not everyone thinks we’re headed for a dystopia.

Some classes of jobs will be handed over to the ‘immigrants’ of AI and Robotics, but more will have been generated in creative and curating activities as demand for their services grows exponentially while barriers to entry continue to fall. For many classes of jobs, robots will continue to be poor labor substitutes. (JP Rangaswami, Pew)

Though inequality could soar in such a world, unemployment would not necessarily spike…Just as past mechanisation freed, or forced, workers into jobs requiring more cognitive dexterity, leaps in machine intelligence could create space for people to specialise in more emotive occupations, as yet unsuited to machines: a world of artists and therapists, love counsellors and yoga instructors. (The Economist)

This strike me as naive. More creative jobs? We already have more art than one could consume in a lifetime, supply >> demand, that’s why the price has dropped to $0—if piracy didn’t exist you still wouldn’t buy music, you’d just download the Bandcamp albums of groups giving it away for free. I’ll concede that anything is possible, but my hunch is that the future will have fewer love counsellors and more unemployed MS Paint artisans smoking weed and watching Netflix. If there was a decent basic income and policy in place to fix the costs of healthcare and education, maybe Netflix-land wouldn’t be the worst place to live in. But on the other hand…

It’s possible to imagine a world in which nobody is happy.

As robots become more and more widespread, low-skill jobs disappear. Many people give up and accept a life of poverty, others are rendered "unemployable” due to disability, since when a thousand people are applying for a job, any mark against you is enough to rule you out.

After sitting in the waiting room of his clinic several mornings in a row, I met Dr. Timberlake. It turns out, there is nothing shifty about him. He is a doctor in a very poor place where pretty much every person who comes into his office tells him they are in pain.

“We talk about the pain and what it’s like,” he says. “I always ask them, ‘What grade did you finish?’”

What grade did you finish, of course, is not really a medical question. But Dr. Timberlake believes he needs this information in disability cases because people who have only a high school education aren’t going to be able to get a sit-down job.

Dr. Timberlake is making a judgment call that if you have a particular back problem and a college degree, you’re not disabled. Without the degree, you are. (NPR)

The few remaining job openings have such fierce competition that parents start preparing their children from the moment of birth: a whole life calculated to create the perfect resume.

Even so, only a tiny fraction of applicants are successful. Those that are hired find that the job is back-breakingly strenuous—if you don’t work 120 hours a week, someone else will—and, despite their success, they are unhappy, unsatisfied, and fearful.

The study is titled “The Joys and Dilemmas of Wealth,” but given that the joys tend to be self-evident, it focuses primarily on the dilemmas. The respondents turn out to be a generally dissatisfied lot, whose money has contributed to deep anxieties involving love, work, and family. Indeed, they are frequently dissatisfied even with their sizable fortunes. Most of them still do not consider themselves financially secure; for that, they say, they would require on average one-quarter more wealth than they currently possess. (The Atlantic)

Dystopia doesn’t require anything as dramatic as “a boot stamping on a human face, forever.” It doesn’t require soma or the samizdat. It doesn’t require robot overlords or the Singularity. All it requires is for you to accept the way the system works and play along.

All it needs is a kid waiting for a marshmallow.

Footnotes

More accurately, The Desire To Pass Somewhat Arbitrary Tests Deemed Important By Cultural Authorities. ↩︎

The most plausible hypothesized effect-of-race-on-intelligence concerns Ashkenazi Jews, who are small in number, have mostly intra-bred throughout history, and might have benefited from a post-Nebuchadnezzar founder effect. However, the relevant adoptive twin studies have not been performed, and it is a possible/probable null hypothesis that high Ashkenazi IQs are the result of a cultural emphasis on rational debate and/or memorizing Talmud. ↩︎

I rarely met the other gifted kids, but I remember being unimpressed. Many of the kids were into Rubik’s cubes and at the annual summer camp these poor boring geniuses would spend three hours a day sitting in the common room and rotating squares over and over, silent except for occasional boasts of quick solves, as if the ability to memorize and execute someone else’s algorithm was the best proof of intelligence, which, I suppose, is what they had been told. ↩︎

Although worth noting that the SAT is timed, and that this strongly selects for some types of intelligence over others. “Slow” is often used synonymously with “dumb” and “quick” with “intelligent,” but this is a poor linguistic analogy: some people are slow to respond but intellectually thorough, weak at multiple-choice speed-guesstimation but able to construct insightful and logically-rigorous answers given time. (The thinking required for “factor the polynomial” is almost totally unrelated to the thinking required for mathematical proofs.) ↩︎

This blog post and its associated study are thrown around a lot in the rationalist community as evidence that “eminent scientists in some fields have average IQs around 150 to 160" and thus: “While it is not true that anyone with a high IQ can or will become a great scientist (certainly other factors like drive, luck, creativity play a role), one can nevertheless easily identify the 95 percent (even 99 percent) of the population for whom success in science is highly improbable. Psychometrics works!” A conclusion that is, fittingly, totally moronic. What the study did was: “Roe devised her own high-end intelligence tests as follows: she obtained difficult problems in verbal, spatial and mathematical reasoning from the Educational Testing Service, which administers the SAT, but also performs bespoke testing research for, e.g., the US military. Using these problems, she created three tests (V, S and M), which were administered to the 64 scientists, and also to a cohort of PhD students at Columbia Teacher’s College.” Did you catch the motte and bailey? Somewhere in the blog post, the meaning of "IQ test” is switched from “a standardized test of reasoning skills that is typically given to children” to “thirty-problem tests made up by a psychologist in the 1950s and given to an n=64 sample of forty and fifty year old adults” and then back again. Ignoring my long list of objections involving the phrase “reproducible findings,” testing adults is not the same as testing kids, and shows nothing about innate ability. “People who have been doing hard logic problems for thirty years are good at logic problems.” Shocking. In other news, practicing something makes you better at it—more at 11. ↩︎

In the field of medicine, there’s mixed evidence for the benefit of diversity in-of-itself, complicated by the intangible benefits of diversity (cross-cultural communication) vs. homogeneity (knowing all the lyrics to Don’t Stop Believin’). I suspect there is some real benefit to diversity, but it’s important to note that affirmative action still makes sense even if there isn’t. ↩︎

Note that even though physician assistants have six fewer years of schooling, can switch specialties with ease, and are significantly happier than MDs, the number of annual PA applicants is still only 40% the number of annual MD applicants—and it’s likely that many of these PA applicants had been previously rejected from MD schools. (And note that there are more PA programs than MD-granting institutions, so this isn’t an availability issue.) ↩︎

I’ll speculate that a similar process can explain the miserable lot of current Ph.Ds. Students spend years studying to pass every test—diploma, baccalaureate, doctorate—and then find that their inelastic demand for academia has led them to an ugly place. "Yet universities have continued to churn out Ph.Ds who, as postdocs, provide cheap labor for the campus labs that draw much-needed research funding, but are given little help in moving on to jobs in which they can teach or run their own labs. The result? Biomedical postdocs — according to the National Institutes of Health, there may be as many as 68,000 of them — are clogging a job market that almost certainly can’t absorb them all. ↩︎

When discussing the labor market, employees are spoken of as the “supply [of labor]” and employers as the “demand [for labor],” so technically I am here talking about the inelasticity of supply. ↩︎

(possible album name???) ↩︎

I think the meta-objection to this essay is that I (the author), due to my perfectionism-induced impostor syndrome, am doing just this, telling the reader “what he wants to hear,” namely that since success is caused by external factors he is no worse than any of those #biodeterminism jerks on LessWrong; to this, I politely reply “Ad hominem,” and “So prove me wrong, nerd.” ↩︎