tb is ephemeral, but sepsis is forever.

December 2, 2015

We are winning the war against transmissible disease.

Between 2000 and 2015, global malaria incidence fell by 37% and malaria mortality rates decreased by 60%. The per year rate of new HIV infections has declined 35% since 2000, and the number of AIDS-related deaths has dropped 42% since 2004. Tuberculosis incidence has fallen 18% since 2000, and the TB death rate dropped 47% between 1990 and 2015. Smallpox and polio have been nigh-eradicated; shigellosis, measles, and diphtheria are on their way out.

I do not want to downplay the significance of these diseases. Globally, the Big Three (malaria, HIV, and TB) and neglected tropical diseases are responsible for more suffering and death than just about anything else. If you want to make a difference, this is where your money and effort should go.

However, we are trending in the right direction[1]. Barring some unforeseen apocalypse, it seems likely that sanitation, education, and vaccination will continue to do their saintly work, and it is thus conceivable that all of the above diseases will one day be eliminated.

Compare:

CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics estimates that, based upon information collected for billing purposes, the number of times people were in the hospital with sepsis or septicemia (another word for sepsis) increased from 621,000 in the year 2000 to 1,141,000 in 2008. (Source)

Between 28 and 50 percent of people who get sepsis die.

Sepsis is the end game of infection. If your body fails to control an infection—any infection, be it influenza, a pimple, or fungal meningitis—then your immune system will freak out, your capillaries will leak, your organs will starve, and you will die.

If we’re so good at fighting transmissible disease, then why is sepsis on the rise?

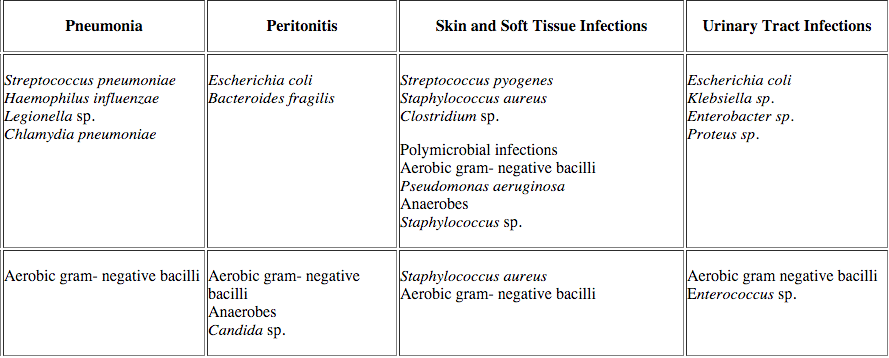

Here are a few of the CDC’s Most Wanted:

Pneumonia is the most common cause of sepsis, and Streptococcus pneumoniae is the most common cause of pneumonia. Strep pneumonia is not very contagious: even if someone French-kisses sputum directly into your bronchioles you probably won’t get sick. Why not? Because the immune system absolutely crushes strep. It has to—Streptococcus pneumoniae is part of the normal human microbiota, and even if it doesn’t live in your throat, you are exposed to it frequently. Yes, some strains are worse than others, hence vaccination, but if you’re an eighty-five year old man on chemotherapy and you get strep pneumonia, the problem isn’t the bacterium, the problem is you.

This is the pattern that explains the future of illness. We’re not getting worse at fighting sepsis—the per-case mortality rate has actually decreased—but people are living longer, the immune system goes caput with age, and eventually we all run out of luck.

Which means that sepsis isn’t going away. The prevalence of fungal sepsis secondary to Candida albicans is increasing, thanks to our weakened immune systems, but we can’t eradicate C. albicans, it’s in our GI tract, it’s in our respiratory tract, it’s on our skin, and even if we did somehow eliminate it, another microbe would instantly take its place. Klebsiella is normal flora, so is Bacteroides, and no one even pretends that we can get rid of E. coli. Pseudomonas aeruginosa, the final boss of opportunistic pathogens, is “found in soil, water, skin flora, and most man-made environments throughout the world”, “thrives not only in normal atmospheres, but also in hypoxic atmospheres”, “uses a wide range of organic material for food”, and has “more than fifty [antibiotic] resistance genes.” This thing is going to survive the heat death of the universe.

It is useful to divide diseases between “self” and “other”: those diseases which are intrinsic to the machinery of the human body, and those which are caused by some external assault. Over the 20th century, medicine made great strides against the “other”: smallpox, polio, asbestos, lead. But sepsis is a disease of the self. Just as cancer results from a failure to control the normally cooperative cells of our body, sepsis results a failure to control our beneficial and commensal microbes. This sort of failure is inevitable as long as we face the inexorable decline of aging.

I’m not saying that we will never beat sepsis, but when we do, we will have changed what it means to be human.

A few sort-of exceptions:

a) Pertussis incidence has been increasing since the 1980s. This may be artificial, secondary to faster diagnosis, or real, due to a change in the pertussis vaccine. Even so, mortality has more than halved since 1990.

b) Syphilis has made a major comeback over the past few years, mostly among men who have sex with men. However, primary syphilis clears up with a shot of penicillin, and mortality rates are far lower than in the past.

c) Cholera prevalence has been stable over the past 20 years, save for a few major outbreaks, e.g. the absolutely horrific one that followed the 2010 earthquake in Haiti. Cholera is spread by food and water contaminated with feces; thanks to sanitation, it is nearly nonexistent in the United States. The fact that cholera still infects 2.9 million people each year is an indictment of our civilization. ↩︎