Questionable Content

July 27, 2016

tagline: “we’ve all been there.”

I.

Washington, DC (January 26, 2015) - It seems harmless: getting settled in for a night of marathon session for a favorite TV show, like House of Cards. But why do we binge-watch TV, and can it really be harmless?

Look, I know this is an easy target. Grant me this one? I’ll aim higher next time.

The researchers conducted a survey on 316 18- to 29-year-olds on how often they watched TV; how often they had feelings of loneliness, depression and self-regulation deficiency; and finally on how often they binge-watched TV. They found that the more lonely and depressed the study participants were, the more likely they were to binge-watch TV, using this activity to move away from negative feelings. (Source)

The amyloid minds at VICE, laying brand on a similar study:

You have met them, the new type of person that has emerged in the last couple of years through the cracks of your classic popular tribes—not quite a hipster, not quite punk or cutester, not an earnest pothead or fuckboy, but something else, something other—The Man Whose Entire Personality Is Built Around Really Liking Breaking Bad.

Well, good news: That man is hideously depressed, and so are we all, because binge-watching TV shows is trouncing our mental health. (VICE)

And now that correlation has blurred with causation:

But the most confounding factor may be how fast the technology that lets us binge is changing. Consider the autoplay function on Netflix. When an episode ends, there’s a 15-second pause and then the next episode in the season starts automatically. There’s no choice in this behavior, which means it’s up to the viewer to regulate themselves and turn off the TV. (NPR)

Thanks, Mom.

Since NPR isn’t willing to bite the bullet, I will: Big Media is forcing autoplay on the American public, giving us depression and diabesity. Big Pharma follows close behind, profiting off the treatment. Then the cash gets funneled to the NRA and makers of 32 ounce soda. Sigh. Pack up the Nespresso, honey. We’re moving to Canada.

II.

Here’s an alternative explanation: people rarely binge-watch in groups. Couples may share a series, but that tends to be a forty minutes per night thing, not the please-plug-me-into-the-Matrix desperation of your seventh consecutive episode of [topical reference]. And if two lovers can’t coordinate bathroom breaks, no way are you gonna get five people to agree on a non-alcoholic activity for more than an hour. Frequent bingers, then, “don’t have anything better to do.” On average: lonely, bored.

For such individuals, maybe binge-watching is palliative, maybe it’s harmful, maybe it depends. Which comes first, the fantasy world or the ruined reality? Further research is needed. Read some sci-fi. Ask your doctor if Love is right for you.

That doesn’t mean binge-watching’s proliferation is unimportant. On the contrary, it indicates a profound shift in our choice of entertainment, and, accordingly, the way we define ourselves.

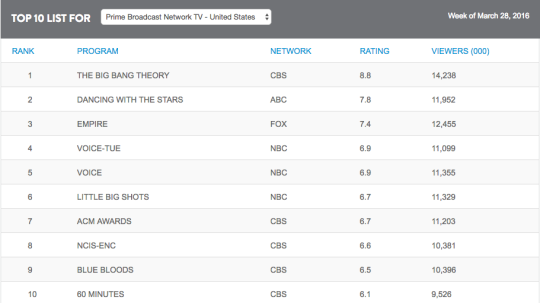

Of the top 10 most-watched broadcast shows, The Voice, Little Big Shots, and Dancing With The Stars are game shows; 60 Minutes is news; The Big Bang Theory is a sitcom; Empire is a soap opera; NCIS and Blue Bloods are police crime dramas.

Aside from Empire, these shows are all procedural: the intra-episode narrative trumps any season-long arc, most episodes can be watched out of order. “If you don’t watch Dancing With The Stars from the beginning, you’re going to miss all the self-referential symbolism in season 3,” said no one ever. Cable TV takes this to the next level: not only is episode order immaterial, it barely matters when you tune in. This encourages group viewing: “Switch on the Colts game, I wanna see who’s winning.” Like pop from an overhead speaker, cable exists to soak up unwanted attention, which is why you’ll find both in YMCAs, sports bars, and urology waiting rooms.

Try to visualize other situations in which procedurals are viewed. Dad drinking news and Coors after work. Mom fading into HGTV on a gloomy day. The family gathered under blankets in the living room, eating whole wheat pasta to signal dominance over a narrated Serengeti.

Procedurals are comfort food. How do you make someone comfortable? Tell them a bedtime story. Status quo, perturbation, status quo. Sheldon/Oprah acknowledges his/her wackiness and everyone hugs. Bill O’Reilly/John Oliver’s indignation subsides, leaving a knowing smile for the ingroup. All hail the peak-end rule.

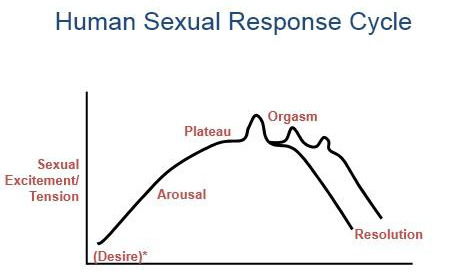

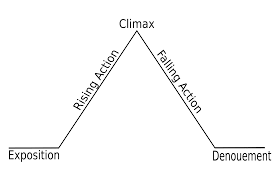

But procedurals have a stark limitation: they won’t let you disappear. The playwright Gustav Freytag divided drama into five acts: exposition, rising action, climax, falling action, and resolution. This is the formula by which humans process stories and thus memories. It can be obscured; it cannot not be escaped. If the story begins in medias res, the opening action becomes exposition. (Example: Star Wars.) If a “climax” happens without prelude or follow-up, it isn’t a climax. (John Travolta’s death in Pulp Fiction.) If the story lacks a proper climax, we connote symbolism on a close-enough moment. (The Sound and the Fury.) And if the story ends without proper denouement, we conjecture a moral and fill in the narrative gap. (A Perfect Day For Bananafish.)

Problem is, this formula is antithetical to binging. When you reach resolution, you have to pause, breathe, and relax, else it’s not resolution. Switching to four-wheel drive and climbing a mountain of exposition requires effort or despondency. Watching back-to-back episodes of the same news program is unpleasant. Three consecutive Friends reruns is grounds for a 5150.

Hence, the serial.

Serials are epitomized by the soap opera, featuring “related story lines about the lives of many characters, usually focusing on emotional relationships to the point of melodrama.” I don’t think fans of The Wire would call it a soap opera, but if you elide drama and melodrama then it meets the above definition. So does Breaking Bad, Game of Thrones, Transparent, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Scandal, Fargo, and ~ any Nussbaum-approved must-watch So Important Netflix Original Series. Sure, some soaps borrow procedural tricks—Bojack wears the forced-grin affectations of a sitcom—but a quick Youtube comment scan proves that fans watch for the character arcs. The slick .jpg above distinguishes between “shows to devour” and “shows to savor”; the actual difference is “completed in four days” vs. “completed in six days.” Which is nothing.

(Even in the pre-streaming era, soap operas were daytime programming, designed to fill time. Contrast with the evening news.)

How do these shows do it? Two plus hours (per night) is a significant investment—many habitual bingers hesitate to sit down for “a whole movie”, and the tenth minute of a Youtube video is mythological. The longer one is immersed, the greater the risk of fantasy disengagement, of Wait, why was I watching this? followed by Shouldn’t I be working on my actual life? followed by a refractory period of self-loathing, muscle weakness, and hummus.

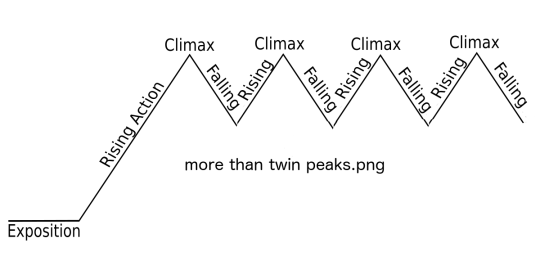

22-minute procedurals permit your mind to wander between punchlines, two-hour soccer matches encourage you to talk with Europeans, serials—binged alone—cannot take any chances with your attention. And to this end, one rule is paramount: never provide the viewer with resolution.

III.

We are dancing around the word “ritual.”

Rituals can be social (various rites of passage) or antisocial (OCD compulsions); pleasant (eating), neutral (wearing a uniform), or unpleasant (cutting). No matter the adjective, the purpose is the same: comfort. Rituals are predictable, predictability allows understanding, understanding allows control, and control is the opposite of anxiety.

The knock against procedurals is that they are predictable, but they have to be, that’s the point. Serials are bound by the same five acts and are almost as predictable—meta-spoiler alert, the show is called Love, it’s about a boy and a girl—except the bass doesn’t drop as planned. We need a fix for the tension the show has created[^1], so we click onwards, only to find a fresh set of obstacles and associated sidequests. Zeno’s paradox on a Kramer entrance. Status quo, perturbation, sine waves forever.

This informs serial structure in both macro and micro. “The in-laws are coming so we have to pretend to be vegans” is a viable sitcom plot, but too simply resolved for a serial arc. Instead, a fundamental wrongness is built into the serial’s world. Pilot episode, every time: the girl is dating the wrong guy, the guy is dating the wrong girl, the protagonist is/was maimed in a horrible accident, Good Male hero is forced to bow to a Bad Male prick. When the big wrong is offscreen, something still needs to block the path to resolution, hence drama, locker-room drama, a special conflict between each and every subset of characters. I’m sure this seems self-evident—“drama has drama”—but note that serials rarely showcase contented friendship, whereas procedural characters get along dandy as they catch criminals/make fun of Manhattanites/find quality housing at an affordable price. Procedurals come with preformed tribes: Mets against Yankees, family feud family, Man vs. Wild. Serials are about individuals.

And, counter- or intuitively, this makes serials aspirational. You might like 30 Rock’s jokes, its philosophy, its characters, but no one thinks, “If only I worked for NBC in the mid-2000s! I would belong.” In contrast, people love to imagine themselves in Westeros or Walking Dead-land, which, though I haven’t been following too closely, seems like kind of a downer place. I’m not saying aspiring Costco warlords think such a life would be pleasant, but neither outrage porn isn’t pleasant and yet you still go on Facebook. “You have it all wrong, I’m mad at the people who post outrage porn.” Oh, cool. I think there’s a subreddit for that.

IV.

Fine, pedants. The line between procedurals and serials is sometimes blurred—reality shows, for example, have season-long narratives but still grant resolution and piano music at the end of each episode. And people watch TV for reasons besides comfort and superstimulus immersion. Some shows carry branding, some shows are didactic, some shows are even, I admit it, “good.” Style is the soul; I’m not radical enough to claim that content is meaningless.

Still, the pattern is strong. And not unique to 16:9.

Viral content—shared amongst a group with context prepackaged—always follows the structure of a procedural. “As a goalie, Jason never let a ball get past him. Then he developed ALL: Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. But, thanks to Memorial Sloan Kettering…” Music videos follow this pattern, bound by the I–IV–V–I and chorus/verse/chorus of the song. So do op-eds, clickbait, and thinkpieces. In a “takedown” or “debunking”, the host parasite gets the first and last words; infographic .jpgs are closed captioning for the talk show formula.

The stories we follow longitudinally become soap operas. Webcomics, blog or vlog archives, celeb goss, rap discographies, folk discographies, group chats, forums, Twitter/Tumblr/Instagram archives. Diary entries of any sort, really—start keeping one and by day four you’ll have drawn yourself a shipping chart.

Two observed trends to correlate with the above.

First: sharing content that is too-broadly procedural (“FWD: FWD: When this little girl starts singing…”) is a dead giveaway that someone is old, sorta uncool, and never allowed to borrow your phone. Conversely, Flomax junkies mock Vyvanse containers for their focus on niche serials. “I just don’t get it. Why would you care what online strangers think about K-Pop?” “Because it’s part of the narrative, Dad! God!” I’m sure housewives still watch soaps, but the majority of modern serials are consumed by young people online.

Second: procedurals are low class. Game shows, cop shows, crap reviews = there’s a reason the Angry Birds movie was advertised at McDonald’s. Honest question: do you know anyone who watches any of the top 10 most-watched broadcast shows? Okay, one person watches Big Bang Theory, but she’s an acquaintance, not a friend. Even your parents are cooler than that—they like Downtown Abbey.

Bonus: have you ever heard of a Republican watching a Netflix Original Series?

V.

Even at their most polemic, procedurals reaffirm the status quo. Oh, maybe not the societal status quo, not directly, FOX and Gawker agree that’s all sorts of messed up. Your status quo. Which amounts to the same thing.

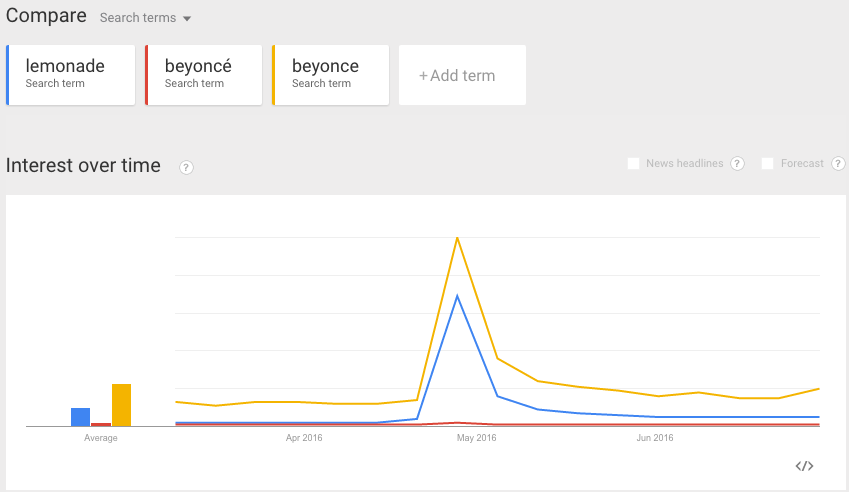

Breaking news breaks for about one week, followed by a week of feeble, bedridden decline. If you don’t believe me, do a Google Trend search for the political scoop of your choice. They all look about the same.

The lifecycle is consistent as well: rumors, media description, tribal rage, measured thinkpieces (“Really, this should teach us empathy”), and dissolution into the sea of history. The parallel is obvious. The logic of stories transcends scale, not by black magic, but because the media gives us what we want. So why does individual interest fade? Think back to a hot-button issue you stopped talking or thinking about, what was your reason? A four-word thought bubble: “Now I get it.”

It doesn’t matter if you actually get/got it, the feeling of understanding equals resolution. Procedurals comfort even if you disagree_._ If Jacobin is always wrong, not-Jacobin must be correct. CDC pamphlets bolster anti-vaxxers, Corinthians on a sunset makes atheists want to go Kratos. No one hatewatches a serial, hatereading a procedural is anxiolytic: “I was lost, but now I know exactly what to feel. Loathing for the outgroup.” A mental punching bag for when mental masturbation isn’t enough.

Consequently, procedurals are terrible missionaries. Typical procedurals propose a status quo, “The One Where [Tribe] Has a [Noun] Problem”, mansplain, and ouroboros back. This is necessary—in a proper ritual, Act 1 has to mirror Act 5—but putting the conclusion up front is discourse arsenic. Consider:

- People who agree with Act 1 will either stop (“Cool, that’s what I thought”) or read until the Act 5 reinforcement. Status quo affirmed.

- People who blindly disagree with Act 1 will stop (“Of course this is what they believe”) or hateread towards Act 5 validation. Status quo affirmed.

- People who disagree with Act 1 but read charitably despite this MAY have their object-level opinions changed. Neat, but zoom out: what motivates these people to move past the first paragraph? “This is awful, but I ought to be open-minded.” Which implies a big-picture belief, an identity—that will be confirmed by the ritual. “I’m glad I read that. Even if I don’t entirely agree, now I get where they’re coming from. Welp, back to my podcast about extraordinary moments in otherwise ordinary lives!” Status quo, etc.

Step away from my castle and dismantle your trebuchets. A nuanced opinion is better than a pixelated one. I am simply pointing out a bug, maybe a feature: procedurals rarely change one’s axioms. Usually the opposite. They are rituals, and rituals tell you what you want to believe.

VI.

At age 6, ideological viruses are transmitted vertically: prompted or not, children try out for team mascot. A decade ago, 3rd-graders proclaimed “Iraq is about oil!” like it came from the CIA’s classified file on puberty; in another town and tax bracket, sunburnt Cub Scouts tell racist and homophobic jokes for the same reason: “These are the people we are supposed to dislike.”

Ideologies happen to children. They do not seek them out. Does anyone?

High school punks start out angry—cystic acne, this town sucks—attend shows where you can punch nephrons, and then stumble upon the CrimethInc slogans that justify their anger. This doesn’t invalidate their politics, I’m not here to argue politics, and anyway I also thought the Anarchist’s Cookbook was hot shit when I was 15. But order of operations implies that beliefs develop, to some extent, by accident. If you start proselytizing Bakunin to a skinned-knee 12 year-old he’ll hit you with a shuriken; at 17 he’s reading Das Kapital on a cracked Samsung to impress a girl with a nose ring. Cool, but you better believe that in 1861 he’d lie about his age to fight for the Confederacy. No one joins reddit to whinge about how Amy Schumer runs the Illuminati, they join to talk about videogames and eventually the memes seep in. Do social media fascists have more in common with a social media marxists or guys with WHITE and POWER tattooed on respective shins? Anyone remember Pokémon Go?

Cults have two goals: keep veterans involved and recruit new members. Rituals accomplish the first task and prevent the second. If you lead with the story of Xenu dropping H-bombs on the Late Cretaceous, you’ve killed any chance of winning over a D-lister. No, you start with:

“What is true is what is true for you. No one has any right to force data on you and command you to believe it or else.”

“If it is not true for you, it isn’t true. Think your own way through things, accept what is true for you, discard the rest. There is nothing unhappier than one who tries to live in a chaos of lies.” (Source)

And then you offer aid: addiction treatment, relationship counseling, personal efficiency seminars—how can Scientology help you? By the way, is anyone else just loving Dianetics?

This is a serial, a soap opera, the plot of every TV series about a sad comedian trying to make it in the big bad world. “I’m smart, I’m sensitive—but I’m troubled. Will anything ever make me happy?” I don’t know, but I guarantee you’ll still have thetans at the end of the first season. Act 1 doesn’t have to match Act 5, so bury the lede and make sure Act 1 is tempting. Think about how a salesman shakes your hand, drops a few compliments, asks where you’re from, tells a story about the place—all before mentioning the product. You know it’s a sales pitch, but somehow that doesn’t bother you until you’ve spent $25 on scented bath salts. Being a salesman isn’t about selling the product, it’s about selling yourself. Willy Loman knew that but made the mistake of starring in a play called Death of a Salesman. If you’re building a brand, save it for the end of the ad.

These are ugly examples, but they speak to a sad desperate beautiful truth: people want to belong. Belonging always precedes belief: you have to be part of {X,Y,Z} in order to even hear about X. Politics and ethics are no different than grammar and etiquette. Stuff we pick up as we learn to fit in.

Our beliefs are not fixed, but change has only one path: prove that you belong in Act 1, and use this shared starting point to argue for a revision of tribal customs. This is the structure of a serial. More generally, it is known as empathy.

This is how I know that any art piece billed as Feminist & Important will, in fact, win exactly zero people over to feminism. This is not a criticism of feminism, nor is it a criticism of the art. It is a criticism of the marketing; it is a criticism of you, pro or anti, for demanding that SEO labels tell you what to want. The media narrative replaces exposition and obviates the conclusion, turning a (persuasive?) (complex?) story into a clickbait headline, a chanted war cry, repulsing anyone who does not already agree. This is true for any ideology: being on the front page of The New York Times is a death knell, it is static friction, it tells everyone who distrusts the Times that they should disagree. Once you step into a church, all you can do is preach to the choir. “Must Watch” means “You already know what you’re going to see.”

Is there hope? Public opinion of same-sex marriage inverted in the 2000s, from 57% opposed in 2001 to 55% in favor in 2016. The people who changed their minds tell a similar story: I had a friend/coworker, mad cool, downed shots like Steph Curry, and it turned out she was a lesbian. Frank Ocean’s Channel Orange coming out letter doesn’t use the words “gay” or “bi”; the album has multiple songs about female lovers but only oblique references to his male, unrequited, love. The message isn’t “Fuck off breeder scum.” It is consciously the opposite: “We are not so different.”

And that’s the catch. Is that what you want, to be “not so different”? To say: “As great as my suffering is, I know you can relate”? To watch your identity become decorative? To see your community dissolved and washed away?

The cost of progress is assimilation. It is painful. Assimilation means competing against the gruesome majority of the human species, and you will be outnumbered and outvoted, and you will have to play by their rules and their values, and most of the time, you will lose. This is the sacrifice that heroism requires: you have to say no to belonging, you have to force yourself to be around people who ignore you, who despise you; you have to be kind to them until they fucking cave.

For everyone else, there’s Netflix.

VII.

Fields of study have intrinsic biases. History is conservative: patterns repeat, competition is progress, it’s no fun rooting for the losing team. Psychology is liberal: once you reduce everything to DNA and environment, judging someone for their choices becomes absurd. Entertainment genres have biases as well: action movies, ft. Objectively Bad Guys, are conservative; tearjerkers, implicitly about society’s failure to support the weak, are liberal.

Procedurals and serials do not have political biases per se. They are weaponized nonetheless. Procedurals resist change, serials promote it. Not any particular type of change—serials simply promise something better.

The subset of people who lose themselves in serials falls entirely within the set of people who are “trying to find themselves.” Young people, educated people, people with options, people with free time, people in therapy. The buzzword is narcissism, but I don’t mean it as an insult. The alternative does not seem better. People who never inhabit other lives are either dangerously sure of themselves or are too survival-occupied to ponder alternative values. The poor, the devout, the sycophantic.

With prosperity, the balance has shifted towards serials. There have always been cults, now anyone can be a cult leader, and that would be fine, except the first item on the agenda is to invent rituals, mandate sacrifices, come up with ways to keep normies out. The problem is not that there are too many tribes. It’s that they are mutually exclusive.

Is binge-watching bad for you? I doubt it. But the current sea change comes with a cost. The ceaseless movement from tribe to tribe, each one vowing a better fit, splits us into factions, balkanizes us into subcultures, and atomizes us towards the logical endgame: a personalized fantasy and a dextrose drip. My fear is not that serials will make us lonely. My fear is that we will become unable to conceive of another human being who could make us feel less alone.

But I don’t need to tell you that. You know how the story goes.

Footnotes

[^1] Probably a coincidence.