Modern Romance

April 1, 2017

everyone needs a little negative space

(spoilers for all movies discussed)

I.

The advertising campaign in the weeks leading up to the 2017 Oscars—that is, the #Oscarsowhite boycott, low budget underdog Moonlight vs. slick self-congratulatory La La Land, lines drawn based on tribal identity; “I even talked to a voter who gave Moonlight his top vote, sight unseen;” tension building up to a stunning (!!) last minute twist; an insipid academy in which Sean Penn is a voting member “held to task” instead of the people with actual power, i.e. the studios, i.e. us, the viewers—was annoying, to say the least.

Even so, I am grateful that I will only have to hear “Best Picture winner” and “La La Land” in the same sentence once.

What does white people courtship look like in the age of the internet? Well, OKCupid and asphyxiation, but it’s hard to make a musical out of that one. So what is romance supposed to look like? According to Hollywood: love is someone who makes it so you never have to talk to anyone else.

1. Other People Don’t Exist

There are only two human beings in La La Land: Ryan Gosling and Emma Stone. Ryan and Emma have motivations (opening a jazz club, acting) and foibles (Warhammer 40K, keyboard duster). The other characters that appear in the film have neither. Ryan’s sister exists only in contrast to him: she is competent so that we can see that he is neurotic. Then she disappears. John Legend plays a pop jazz player so that Ryan can look downcast and mumble something about plebs. Emma Stone’s roommates wear red, green, and yellow, so that Emma can wear blue.

The film’s closest pass at non-solipsism is the opening number, in which a group of diverse and unrealistically polite Los Angelenos sing about coming to the city to chase their dreams.

[Young Man]

I hear ‘em ev’ry day

The rhythms in the canyons

That’ll never fade away

The ballads in the barrooms

Left by those who came before

They say “you gotta want it more”

So I bang on ev’ry door

[Young Woman]

And even when the answer’s “no”

Or when my money’s running low

The dusty mic and neon glow

Are all I need

The film preempts the critique “how can you make a film about two white people navel gazing in the year 2016?” with this song’s answer, “because everyone else is exactly the same.” Doubtful, but whatever—note that these traffic-bound palette swaps once again redound on Ryan & Emma. Transitive property: if our heroes succeed, so does the whole world.

Of course, it’s not La La Land’s job to be Synecdoche, Los Angeles. There’s nothing wrong with making a romance that focuses very closely on the two leads—the Before Sunrise trilogy comes to mind. But even in those movies, the bit parts seemed to have existences independent from the main characters: an old couple fighting on the train, a disheveled poet smoking on the waterfront. No one in La La Land seems to understand object permanence. Perhaps that’s why they don’t have any friends.

2. Authenticity Is All You Need

Here’s a plot that doesn’t get used anymore: boy lies to girl, girl grows to like boy, lie is revealed, girl is heartbroken, boy renounces lie, boy proves his love by defeating Jack Black in a breakdancing competition, reconciliation, happy ending.

I’ll grant that the above plot is awful, and I don’t recommend that you base your relationships on deceit or anything else from the 90s. But you have to give that guy credit for trying. In La La Land, Emma has to make the first move, twice, for the plot to advance. Ryan then takes Emma to a jazz club (his interest) and invites her to see Rebel Without a Cause (also his interest). I’m not hating, Ryan Gosling is a charming man, they have chemistry, do what thou wilt, I’m just noting a cultural trend. In the olden days, the guy developed a crush and had to “win” the girl; in La La Land, the girl is attracted to the guy’s character sheet, and the plot/romance advances as the guy lets her into his world. (You’re The Worst is a good example of the same, as is Fifty Shades of Grey. Consider whether this represents an increase or decrease in female sexual power.)

This makes Emma Stone, despite her pellegrino bubbliness, the opposite of a Manic Pixie Dream Girl.

”…that bubbly, shallow cinematic creature that exists solely in the fevered imaginations of sensitive writer-directors to teach broodingly soulful young men to embrace life and its infinite mysteries and adventures.“ (Wiki)

Rather than convince [brooding, soulful] Ryan Gosling to join Zoroastrianism and wear PLUR bracelets, Emma Stone encourages him to go deeper into his narrowly defined dream. “If the masses don’t get it, so be it!” Thank God this isn’t a Darren Aronofsky film. And Ryan does the same for her—in light of Emma’s failed auditions, he advises her to write a one-woman play, a suggestion that in most states is legal grounds for divorce.

But since this is Hollywood, literally and figuratively, both of them become wildly successful.

3. A Sense Of An Ending

Spoiler alert, Ryan and Emma don’t end up together. They get something much better.

In the final scene, Emma (now a famous actress) and her husband (generic dude) stumble into Ryan’s jazz club. He shoots her a glance (“this could be us, but you playin’”), taps out the recurring musical motif, and triggers a five minute Mulholland Drive dream sequence in which Emma imagines their hypothetical life together in space and etc. Look of mutual acknowledgement. Close.

The sad end was inevitable, just ask Titanic, happy endings aren’t nearly as Oscar-worthy. A happy ending raises questions, namely, what next? Kids? Montessori schools? Home Depot? Chablis? Book club? Will you be able to sustain the passion that brought you this far? That’s not romantic, that’s terrifying.

The sad ending lets you idealize the relationship, imagining the emotional peaks without having to reckon with the flatline. And for the same reason, the sad ending serves as a lasting reminder of your own power. “I had her when she was beautiful. And I was the best she ever had.” Lost in her own memories, she’s never going to tell you different.

II.

As usual, there’s a person to blame for all this, and that person is Sofia Coppola.

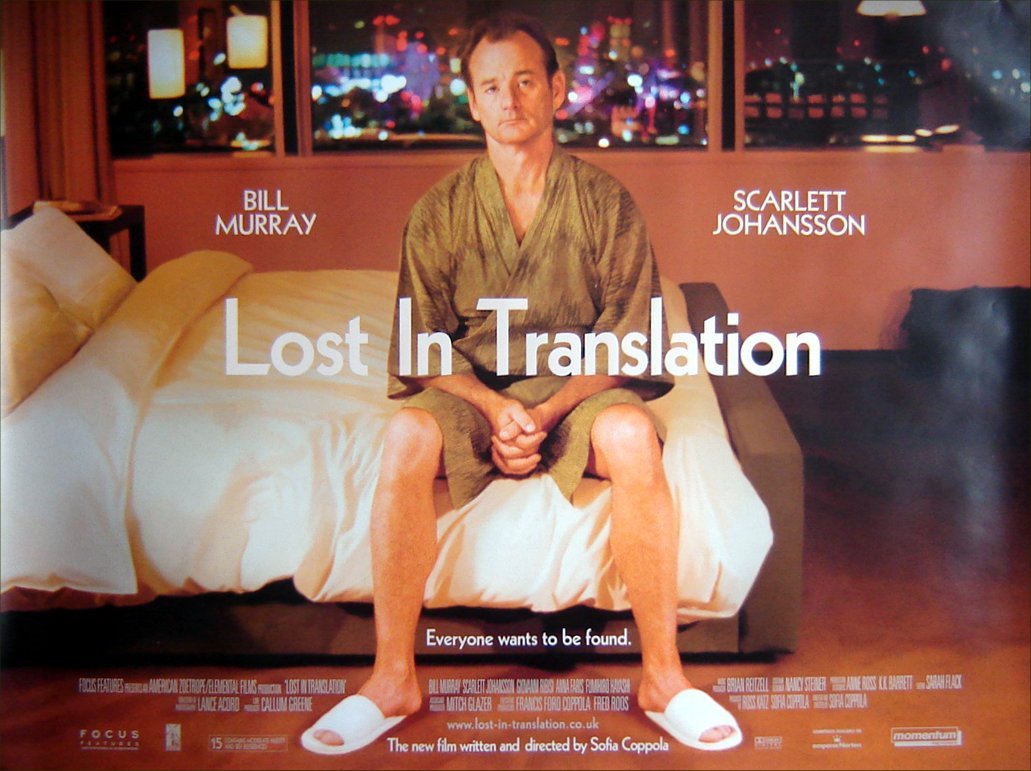

Every one of the above tropes was codified by Lost In Translation. Most of the side characters didn’t speak English, so no way were they going to get a second dimension. The movie is obsessed with authenticity: Scar Jo picks Bill Murray because he sees through the facade of whiskey commercials (unlike the Japanese, or her husband); Bill Murray escapes his fabric-cataloguing wife; the two of them retreat into each other’s company in lieu of the outside world. And the ending—Bill Murray whispers something unheard, kisses his co-star, and the two of them part ways, leaving behind a bittersweet yet somehow self-aggrandizing memory.

Lost In Translation wasn’t a musical, but its aesthetic was music video, shoegaze guitars and long dialogue-free shots of cityscape, #dream, #urban, #intimate. The movie’s descendants (Her being the closest mimic) are no less dependent on the fuzz pedal. Like a Valentine’s day mixtape, like an album put on pre-coitus, the music is chosen not to set the mood, but to soundtrack the scene for your future self. “When I look back on this, I want to feel…”

This is nice in small doses, sure. Lost In Translation had some good parts. La La Land wasn’t my brand, but I can’t knock the craft—the camera did some sick ollies, the song and dance routine was probably great if you’re into platonic cuddling and Apples to Apples. I don’t think these are bad movies, I just think you should be aware of what your unconscious is signing up for.

The underlying assumption of these films is that romance is best experienced in retrospect. You can spot the victims of this worldview by their Uniqlo flannel and sensitive eyes, constantly mourning some shower sex long past, lonely and even more so around others, unable to enjoy relationships until they implode, because then and only then are they understandable as stories. The underlying assumption is that if you wait long enough, love will find you, validate your disconnection from the human species, and depart without asking anything in return. These aren’t romance movies, they’re movies about the romance of movies. The comfort only lasts as long as the lights are dimmed.