In Praise of Heuristics: Clinical Intuition

November 8, 2015

sick or not sick?

(content warnings: medical talk, conjecture, video of a sick kid)

I.

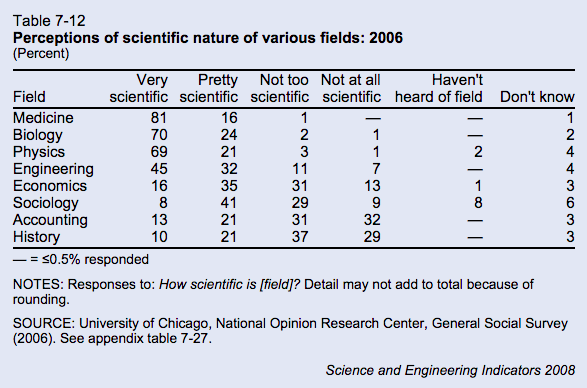

In a 2006 survey from the National Opinion Research Center, the public voted that medicine was the “most scientific” field, above biology, physics, or engineering.

When the survey surfaced in the rationalist community, it was immolated with criticism. From the relevant blog post:

There is simply no way that medicine is more scientific than physics. Perhaps I have a very narrow view of what science is (e.g., prediction & precision), but it’s an alternate universe where medicine is more scientific than physics, end of story.

And from the comments:

People want to believe that medicine is very scientific, and so they do – despite medicine being astoundingly unscientific in most of its aspects. Once again, we find that the data can be explained by referring to a simple fact: people are dumb.

I agree that (clinical) medicine is less scientific than physics, but I think it’s worth exploring what we mean by “scientific.” Is it the use of the scientific method, in particular, hypothesis testing? Is it a willingness to follow research evidence, even in the face in existing dogma? Or is “prediction and precision,” keenness of methodology, big machines, big samples, and tiny p-values? Because I think medicine has good excuses for all three definitions. Medicine may be irrational, but it’s irrational for perfectly rational reasons.

- Lack of hypothesis testing.

The majority of medical research relies on correlation, which can be subtle, requiring a large sample size, and delayed, requiring longitudinal studies. (“If we control for everything else, people on aspirin have fewer heart attacks.”) The field of medicine is risk averse (something about doing no harm), some diseases are rare, and side effects are not always obvious. Hypothesis-testing is easier for physicists, Large Hadron Collider excepted.

- Failure to follow the evidence.

If a doctor’s job was simply to treat the immediate disease, medicine might be closer to physics, but physicians are expected to perform a nebulous mix of “treat the current disease,” “avoid long term side effects,” “reduce costs,” “maintain patient satisfaction,” and “don’t get sued.” Prescribing antibiotics for a cold might not be an evidence-based treatment, but it’s an evidence-based way to improve patient satisfaction.[1]

- Insufficient precision.

Medicine does not prize epistemology above all else. No one would criticize physics research for being “too thorough,” but MD’s are constantly reminded that ordering too many diagnostic tests is a problem, both due to expense and because the tests themselves can harm the patient (e.g. radiation exposure). Some conditions (e.g. Alzheimer’s, multiple sclerosis) have no gold standard test other than autopsy, and many more are dangerous enough that treatment must be started before the workup is complete. Doctors are thus forced to use an gestalt of the patient’s story, the physical exam, diagnostic tests, and—cue theme song from House—clinical intuition.

“System 1” thinking is intuitive thinking – fast, automatic and emotional – and based on simple mental rules of thumb (“heuristics”) and thinking biases (cognitive biases) that result in impressions, feelings and inclinations.

In contrast, “System 2” thought processes are deliberately controlled, effortful, intentional, and require justification via logic and evidence. (Source)

Intuition, emotion, heuristics—I don’t blame academic scientists for getting the heebie-jeebies. Aside from medicine, no scientific field accepts intuition as a valid component of reasoning, and rightfully so. (“P doesn’t equal NP—you’ll just have to trust me on this one.”) But clinical intuition ain’t all that bad.

Within the 13 comorbid disease groups, and within the 15 basic categories of reason for admission, the physicians’ severity ratings were the most significant predictor of in-hospital mortality. Death rates rose from 0% in those rated as not ill, to 2% in the mildly ill, to 6% in the moderately ill, to 23% in the severely ill, and to 58% in those rated as moribund (p < 0.001). Sickness ratings also predicted time to death: mildly ill patients died after prolonged hospitalizations, while the moribund died shortly after admission.

The patients’ age, sex, race, the number of comorbid diseases or problems did not predict mortality. Patients with serious comorbidity (metastases, AIDS, or cirrhosis) had a higher mortality rate than other patients (p < 0.001); however, the severity ratings predicted outcomes within this group (p < 0.001) as well as among those without such serious comorbidity (p < 0.001). (Source).

The (limited) evidence shows that clinical intuition is consistently accurate for some conditions (e.g. viral warts), consistently inaccurate for others (e.g. neonatal jaundice), and good-but-not-perfect for chest pain. Intuition is probably best for big picture, “sick or not sick” decisions. At the top of this article, there’s a stock photo of a kid who is clearly not ill. How about this kid?

Sick.

You can come up with retrospective reasons why this viral video star looks ill—decreased activity, costal retractions, increased work of breathing—but within six seconds of starting the video, you knew that something was wrong.

A total of 3981 children were included in the study, of which 31 were admitted to hospital with a serious infection (0.78%). Accuracy of signs and symptoms was fairly low…The sign paramount in all trees was the physician’s statement ‘something is wrong’. (Source)

The most prominent diagnostic signs in seriously ill children were changed behaviour, crying characteristics and the parents’ opinion…The parents found this illness different from previous illnesses, because of the seriousness or duration of the symptoms, or the occurrence of a critical incident. Classical signs, like high fever, petechiae or abnormalities at auscultation were helpful for the diagnosis when they were present, but not helpful when they were absent. (Source)

Let me be clear: I am not arguing that intuition is a mystical force beyond human comprehension, and I’d rather die than endorse dualism. I just saying that human beings are good at recognizing patterns, and that recognition of a pattern often occurs before we can elucidate the individual data points.

Example: a 45 year old caucasian male with history of MI and stroke is is brought in by ambulance with confusion, slurred speech, and ataxia. Last seen normal yesterday. In the ED, patient is nonverbal but will open his eyes briefly in response to painful stimuli. Exam otherwise unremarkable, blood sugar normal to medics, vital signs within normal limits.

What’s the missing piece? What does the patient look like?

Because if the patient has an NPR t-shirt and three iPad-wielding family members at the bedside, the treatment plan is very different than if he has poor dentition and “ONLY GOD CAN JUDGE ME” tattooed on his chest. I don’t think there’s a study on teardrop tattoos as a diagnostic sign, nevertheless, every time I’ve seen the latter presentation, the ER doctor has said “Oh, must be heroin,” ordered the antidote, and watched the guy recover within fifteen minutes.[2]

And clinical judgment is as useful to determine “not sick” as it is for “sick.” Patients lie, exaggerate, overreact, and get things wrong. I don’t know of any protocols for the maintenance of an effective bullshit detector, but if an ER doc doesn’t know the difference between a 10/10 headache and a “10/10″ headache, then he’s going to spend a lot of time and money treating nonexistent illness.

My point is not that intuition should supplant methodical reasoning, but that it is a necessary adjunct. Human beings are not computers, and our calculations are slow and imperfect. Medicine may not be scientific, but trying to be purely analytic won’t necessarily make medicine better. We don’t need to abandon intuition, we need to get better at it.

And so suppose there was a field of study that required researchers to make predictions about other human beings. Suppose these researchers had to guess not only sick or not sick, but happy or unhappy, thoughtful or bored, loyal or selfish, attracted or ambivalent. Suppose these researchers had to make these assessments rapidly and off of limited information: no control group, limited sample size, just brief snippets of observational data. Would this field be closer to medicine or physics?

Footnotes

As a particularly chilling study illustrates: “In a nationally representative sample, higher patient satisfaction [the top 25%] was associated with less emergency department use but with greater inpatient use, higher overall health care and prescription drug expenditures, and increased mortality.” n.b: Everything is terrible. ↩︎

Pedantic note: the classic giveaways for heroin OD are track marks and constricted pupils, but the last overdose patient I saw had no obvious track marks and normal pupils. Presumably he had smoked methamphetamine, which dilates pupils, prior to OD’ing on heroin. ↩︎